I. As all other arts and sciences have in view some natural good to be obtained, as their proper end, Moral Philosophy, which is the art of regulating the whole of life, must have in view the noblest end; since it undertakes, as far as human reason can go, to lead us into that course of life which is most according to the intention of nature, and most happy, to which end whatever we can obtain by other arts should be subservient. Moral Philosophy therefore must be one of these commanding arts which directs how far the other arts are to be pursued.1 As, however, a common suggestion or natural judgment tells us that happiness, or the means to obtain it, consists in some affection or habit of the soul and in the consequent actions, and since all Philosophers, even of the most opposite schemes, agree in words at least, that “Happiness either consists in virtue and virtuous offices, or is to be obtained and secured by them”.2 The chief points to be enquired into in Morals (Moral Philosophy) must be, what course of life is according to the intention of nature? wherein consists happiness? and what is virtue?3

All such as believe that this universe, and human nature in particular, was formed by the wisdom and counsel of a Deity, must expect to find in our structure and frame some clear evidences, shewing the proper business of mankind, for what course of life, what offices we are furnished by the providence and wisdom of our Creator, and what therefore are the proper means of happiness. We must therefore search accurately into the constitution of our nature, to see what sort of creatures we are; for what purposes nature has formed us; what character God our Creator requires us to maintain. Now the intention of (God and) nature with respect to us, is best known by examining what these things are which our natural senses or perceptive powers recommend to us, and what the most excellent among them? and next, what are the aims of our several natural desires, and which of them are of greatest importance to our happiness? In this inquiry we shall lightly pass over such natural powers as are treated of in other arts [sciences], dwelling chiefly upon those which are of consequence in regulating our morals.

In this art, as in all others, we must proceed from the subjects more easily known, to those that are more obscure; and not follow the priority of nature, or the dignity of the subjects: and therefore don't deduce our first notions of duty from the divine Will; but from the constitution of our nature, which is more immediately known; that from the full knowledge of it, we may discover the design, intention, and will of our Creator as to our conduct [affections and actions].4 Nor will we omit such obvious evidences of our duty as arise even from the considerations of our present secular interests; tho' it will perhaps hereafter appear, that all true virtue must have some nobler spring than any desires of worldly pleasures or interests.

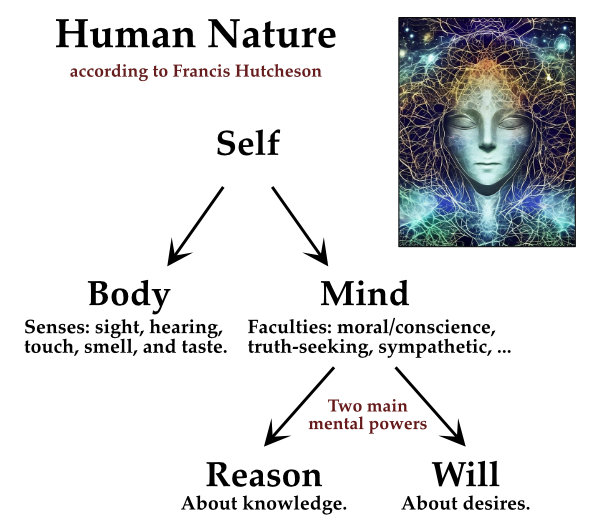

II. First then, Human nature consists of soul and body, each of which has its proper powers, parts, or faculties. The inquiry into the body is more easy, and belongs to the Physicians. We only transiently observe, that it is plainly of a more noble* structure than that of other animals. It has not only organs of sense and all parts requisite either for the preservation of the individual or of the species, but also such as are requisite for that endless variety of action and motion, which a rational and inventive spirit may intend, and these organs formed with exquisite art. One cannot omit the dignity of its erect form, so plainly fitted for enlarged contemplation; the easy and swift motions of the joints; the curious structure of the hand, that great instrument of all ingenious arts; the countenance, so easily variable as to exhibit to us all the affections of the soul; and the organs of voice, so nicely fitted for speech in all its various kinds, and the pleasure of harmony. These points are more fully explained by Anatomists.

This curious frame of the human body we all see to be fading and perishing; needing daily new recruits by food, and constant defence against innumerable dangers from without, by cloathing, shelter, and other conveniencies. The charge of it therefore is committed to a soul endued with forethought and sagacity, which is the other, and by far the nobler part in our constitution.

III. The parts or powers of the soul, which present us with a more glorious view, are of various kinds:† but they are all reducible to two classes, the Understanding and the Will.5 The former contains all the powers which aim at knowledge; the other all our desires pursuing happiness and eschewing misery.

[Hutcheson uses "soul" rather than "mind" and "the understanding" rather than "reason".]

We shall but briefly mention the several operations of the understanding, because they are sufficiently treated of in Logicks and Metaphysicks. The first in order are the senses: under which name we include every “constitution or power of the soul, by which certain feelings, ideas or perceptions are raised upon certain objects presented.” Senses are either external, or internal and mental. The external depend on certain organs of the body, so constituted that upon any impression made on them, or motion excited, whether by external impulses or internal forces in the body, a certain feeling [perception] or notion is raised in the soul. The feelings [perceptions] are generally either agreeable, or at least not uneasy, which ensue upon such impressions and changes as are useful or not hurtful to the body: but uneasy feelings ensue upon those which are destructive or hurtful.6

Tho' bodily pleasure and pain affect the soul pretty vehemently, yet we see they (usually) are of short duration and fleeting; and seldom is not the bare remembrance of past bodily pleasures agreeable, nor the remembrance of past pain in it self uneasy, when we apprehend no returns of them.

By these senses we acquire the first notions of good and evil.7 Such things as excite grateful sensations of this kind, we call good; what excites painful or uneasy sensations, we call evil. Other objects also when perceived by some other kinds of senses, exciting also agreeable feelings, we likewise call good, and their contraries evil. Happiness in general, is “a state wherein there is plenty of such things as excite these grateful sensations of one kind or other, and we are free from pain.” Misery consists in “frequent and lasting sensations of the painful and disagreeable sorts, excluding all grateful sensations.”

There are also certain perceptions dependent on bodily organs, which are of a middle nature as to pleasure or pain, having a very small degree of either joined immediately with them: these are the perceptions by which we discern the primary qualities of external objects and any changes befalling them, their magnitude, figure, situation, motion or rest: all which are discerned chiefly by sight or touch, and give us neither pleasure nor pain of themselves; tho' they frequently intimate to us such events as occasion desires or aversions, joys or sorrows.8

Bodily pleasures and pains, such as we have in common with the brutes, are of some importance to our happiness or misery. The other class of perceptions, which inform us of the qualities and states of things external to us, are of the highest use in all external action, in the acquiring of knowledge, in learning and practising the various arts of life.

Both these kinds of external perceptions may be called direct and antecedent, because they presuppose no previous ideas or forms. But there's another class of perceptions employed about the objects of even the external senses, which for distinction we call reflex or subsequent, because they naturally ensue upon other ideas previously received: of these presently. So much for external sensation.

IV. Internal senses are those powers or determinations of the mind, by which it perceives or is conscious of all within itself, its actions, passions, judgments, wills, desires, joys, sorrows, purposes of action. This power some celebrated writers call consciousness or reflection, which has for its objects the qualities, actions or states of the mind itself, as the external senses have things external. These two classes of sensation, external and internal, furnish our whole store of ideas, the materials about which we exercise that noblest power of reasoning peculiar to the human species. This also deserves a fuller explication, but it belongs to Logick.9

'Tis by this power of reason, that the soul perceives the relations and connexions of things, and their consequences and causes; infers what is to ensue, or what preceded; can discern resemblances, consider in one view the present and the future, propose to itself a whole plan of life, and provide all things requisite for it.

By the exercise of reason it will easily appear, that this whole universe was at first framed by the contrivance and counsel of a most perfect intelligence, and is continually governed by the same; that it is to him mankind owe their preeminence above other animals in the power of reason, and in all these excellencies of mind or body, which clearly intimate to us the will of our munificent Creator and Preserver and shew us what sort of offices, what course of life he requires of us as acceptable in his sight.

V. Since then every sort of good which is immediately of importance to happiness, must be perceived by some immediate power or sense, antecedent to any opinions or reasoning: (for 'tis the business of reasoning to compare the several sorts of good perceived by the several senses, and to find out the proper means for obtaining them:) we must therefore carefully inquire into the several sublimer perceptive powers or senses; since 'tis by them we discover what state or course of life best answers the intention of God and nature, and wherein true happiness consists. But we must premise some brief consideration of the Will, because the motions of the will, our affections, desires and purposes, are the objects of these more subtile senses, which perceive various qualities and important differences among them.

As soon as the mind has got any notion of good or evil by grateful or uneasy sensations of any kind, there naturally arise certain motions of the Will, distinct from all sensation; to wit, Desires of good, and Aversions to evil. For there constantly appears, in every rational being, a stable essential propensity to desire its own happiness, and whatever seems to tend to it, and to avoid the contraries which would make it miserable. And altho' there are few who have seriously inquired what things are of greatest importance to happiness; yet all men naturally desire whatever appears to be of any consequence to this end, and shun the contrary: when several grateful objects occur, all which it cannot pursue together, the mind while it is calm, and under no impulse of any blind appetite or passion, pursues that one which seems of most importance. But if there should appear in any object a mixture of good and evil, the soul will pursue or avoid it, according as the good or the evil appears superior.

Beside these two calm primary motions of the Will, desire and aversion, there are other two commonly ascribed to it, to wit, Joy and Sorrow. But these two are rather to be called new states, or finer feelings or senses of the soul, than motions of the will naturally exciting to action. In this manner however we make up these four species mentioned by the antients, all (specially) referred to the Will, or rational appetite: when good to be obtained is in view, there arises Desire; when evil to be repelled, Aversion: when good is obtained or evil avoided, arises Joy; when good is lost, or evil befallen us, Sorrow.10

VI. But beside the calm motions or affections of the soul and the stable desire of happiness, which employ our reason for their conductor, there are also others of a very different nature; certain vehement turbulent Impulses, which upon certain occurrences naturally agitate the soul, and hurry it on with a blind inconsiderate force to certain actions, pursuits,

or efforts to avoid, exerted about such things as we have never deliberately determined to be of consequence to happiness or misery. Any one may understand what we mean by these blind impetuous motions who reflects on what he has felt, what violent propensities hurried him on, when he was influenced by any of the keener passions of lust, ambition, anger, hatred, envy, love, pity, (delight) or fear; without any previous deliberate opinion about the tendency of these objects or occurrences which raised these several passions to his happiness or misery. These passions are so far from springing from the previous calm desire of happiness, that we find them often opposing it, and drawing the soul contrary ways.11

or efforts to avoid, exerted about such things as we have never deliberately determined to be of consequence to happiness or misery. Any one may understand what we mean by these blind impetuous motions who reflects on what he has felt, what violent propensities hurried him on, when he was influenced by any of the keener passions of lust, ambition, anger, hatred, envy, love, pity, (delight) or fear; without any previous deliberate opinion about the tendency of these objects or occurrences which raised these several passions to his happiness or misery. These passions are so far from springing from the previous calm desire of happiness, that we find them often opposing it, and drawing the soul contrary ways.11

These several passions (violent motions of the soul) the antients reduce to two classes, to wit, the passionate Desires, and the correspondent Aversions; both which they teach to be quite distinct from the Will; the former aiming at the obtaining some pleasure or other, and the latter the warding off something uneasy. Both are by the schoolmen said to reside in the sensitive (or irrational) appetite; which they subdivide into the* concupiscible and irascible; and their impulses they call Passions. The sensitive appetite is not a very proper name for these determinations of the soul, unless the schoolmen would use the word senses in a more extensive signification, so as to include many perceptive powers of an higher sort than the bodily senses. For 'tis plain that many of the most turbulent passions arise upon certain occurrences which affect none of the external senses; such as ambition, congratulation, malicious joy, the keen passions toward glory and power, and many others, with the turbulent aversions to their contraries. The schoolmen however refer to this sensitive appetite all the vehement inconsiderate motions of the will, which are attended with confused uneasy sensations, whatever their occasions be.

Of these passions there are four general classes: such as pursue some apparent good are called passionate Desires or Cupidity; such as tend toward off evil are called Fears, or Anger; such as arise upon obtaining what was desired or the escaping evil, are turbulent Joys; and what arise upon the loss of good, or the befalling of evil, Sorrows. [nor have we in our language words appropriated so as to distinguish between the several calm and passionate motions of the will.]12 Of each class there are many subdivisions according to the variety of objects about which they are employed, which (have very familiar names and) will be further explained hereafter.

VII. There's also another division of the motions of the will whether calm or passionate, according as the advantage or pleasure in view is for ourselves or others.13 That there is among men some disinterested goodness, without any views to interests of their own, but pursuing ultimately the interests of persons beloved, must be evident to such as examine well their own hearts, the motions of friendship or natural affection; and the love and zeal we have for worthy and eminent characters: or to such as observe accurately the cares, the earnest desires, of persons on their deathbeds, and their friendly offices to such as they love even with their last breath: or, in the more heroic characters, their great actions and designs, and their marching willingly and deliberately to certain death for their children, their friends, or their country.

The disinterested affections are either calm, or turbulent and passionate, even as the selfish in which one pursues what seems advantageous or pleasant to himself. And the several affections or passions, whether more simple or complicated, have a variety of names as their objects are various, as they regard one's self, or regard others, and their characters, fortunes, endearments, and the several social bonds with us or with each other; or (on the contrary) the enmities or dissentions by which they are set at variance; or as their former conduct or designs have occasioned these events which excite our passions.14 These particular kind passions are quite different from any calm general good-will to mankind, nor do they at all arise from it. They naturally arise, without premeditation or previous volition, as soon as that species or occasion occurs which is by nature adapted to raise them. We shall have a more proper place to explain them a little further after we have mentioned the more sublime perceptive powers; without the knowledge of which many motions of the will must remain unknown [unintelligible].

What any sense immediately relishes is desired for itself ultimately; and happiness must consist in the possession of all such objects, or of the most important and excellent ones. But when by the use of our reason we find that many things which of themselves give no pleasure to any sense, yet are the necessary means of obtaining what is immediately pleasant and desirable, all such proper means shall also be desired, on account of their ends. Of this class are, an extensive influence in society, riches, and power.

But as beside the several (natural) particular passions of the selfish kind15 there is deeply rooted in the soul a steddy propensity or impulse toward its own highest happiness, which every one upon a little reflection will find, by means whereof he can repress and govern all the particular selfish passions, when they are any way opposite to it; so whosoever in a calm hour takes a full view of human nature, considering the constitutions, tempers, and characters of others, will find a like general propension of soul to wish the universal prosperity and happiness of the whole system. And whosoever by frequent impartial meditation cultivates this extensive affection, which the inward sense of his soul constantly approves in the highest degree, may make it so strong that it will be able to restrain and govern all other affections, whether they regard his own happiness or that of any smaller system or party.16

VIII. Having given this summary view of the Will, we next consider these senses we called reflex or subsequent, by which certain new forms or perceptions are received, in consequence of others previously observed by our external or internal senses; and some of them ensuing upon observing the fortunes of others, or the events discovered by our reason, or the testimony of others. We shall only transiently mention such of them as are not of much importance in morals, that we may more fully explain those which are more necessary.17 The external senses of Sight and Hearing we have in common with the Brutes: but there's superadded to the human Eye and Ear a wonderful and ingenious Relish or Sense,18 by which we receive subtiler pleasures; in material forms gracefulness, beauty and proportion; in sounds concord and harmony; and are highly delighted with observing exact Imitation in the works of the more ingenious arts, Painting, Statuary and Sculpture, and in motion and Action; all which afford us far more manly pleasures than the external senses. These are the Pleasures to which many arts both mechanic and liberal are subservient; and men pursue them even in all that furniture, those utensils, which are otherways requisite for the conveniency of life. And the very grandeur and novelty of objects excite some grateful perceptions not unlike the former, which are naturally connected with and subservient to our desires of knowledge. Whatever is grateful to any of these perceptive powers is for it self desirable, and may on some occasions be to us an ultimate end. For, by the wise (and benevolent) contrivance of God, our senses and appetites are so constituted for our happiness, that what they immediately make grateful is generally on other accounts also useful, either to ourselves or to mankind.

Among these more humane pleasures, we must not omit that enjoyment most peculiarly suited to human nature, which arises from the discovery of Truth, and the enlarging of our knowledge; which is ultimately desirable to all; and is joyful and pleasant in proportion to the dignity of the subject, and the evidence or certainty of the discovery.19

IX. There are other still more noble senses and more useful: such is that sympathy or fellow-feeling,20 by which the state and fortunes of others affect us exceedingly, so that by the very power of nature, previous to any reasoning or meditation [purpose], we rejoice in the prosperity of others, and sorrow with them in their misfortunes; as we are disposed to mirth when we see others chearful, and to weep with those that weep, without any consideration of our own Interests. Hence it is that scarce any man can think himself sufficiently happy tho' he has the fullest supplies of all things requisite for his own use or pleasure: he must also have some tolerable stores for such as are dear to him; since their misery or distresses will necessarily disturb his own happiness.

By means of this sympathy and of some disinterested affections, it happens, as by a sort of contagion or infection, that all our pleasures, even these of the lowest kind, are strangely increased by their being shared with others. There's scarce any chearful or joyful commotion of mind which does not naturally require to be diffused and communicated. Whatever is agreeable, pleasant, witty, or jocose naturally burns forth, and breaks out among others, and must be imparted. Nor on the other hand is there any thing more uneasy or grievous to a man than to behold the distressing toils, pains, griefs, or misery of others, especially of such as have deserved a better Fate.

X. But further: that man was destined by nature for action plainly appears by that multitude of active instincts and desires natural to him; which is further confirmed by that deeply implanted sense approving or condemning certain actions. The soul naturally desires action; nor would one upon any terms consent to be cast into a perpetual state of sleep, tho' he were assured of the sweetest dreams. If a sleep like that of Endymion* were to befall ourselves or any person dear to us, we would look upon it as little better than Death. Nature hath therefore constituted a certain sense or natural taste to attend and regulate each active power, approving that exercise of it which is most agreeable to nature and conducive to the general Interest. The very brute animals, tho' they have none of these reflex senses we mentioned, yet by certain instincts, even previously to any experience or prospect of pleasure, are led, each according to its kind, to its natural actions, and finds in them its chief satisfactions or at least are subservient to their particular happiness. Human nature is full of like instincts; but being endued with reason and the power of reflecting on their own sentiments and conduct, they have also various reflex senses with a nice discernment and relish of many things which could not be observed by the grosser senses, especially of the exercise of their natural powers.21 By these senses that application of our natural powers is immediately approved which is most according to the intention of nature, and which is most beneficial either to the individual or to mankind; and all like application by others is in like manner approved, and thus made matter of joy and glorying. In the very posture and motion of the body, there is something which immediately pleases, whether in our own, or that of others: in the voice and gesture, and the various abilities of body or mind, in the ingenious arts of imitation (already mentioned>, in external actions and exercises, whether about serious business or recreations, we discern something graceful and manly, and the contrary ungraceful and mean, even without any appearance of moral virtue in the one, or vice in the other. But still it is chiefly in these abilities and exercises which are peculiar to mankind that grace and dignity appear; such as we have in common with beasts appear of less dignity. And among the human pursuits which yet are different from moral [voluntary]22 virtues, the pursuits of knowledge are the most venerable. We are all naturally inquisitive and vehemently allured by the discovery of truth. Superior knowledge we count very honourable; but to mistake, to err, to be ignorant, to be imposed upon, we count evil and shameful.

But to regulate the highest powers of our nature, our affections and deliberate designs of action in important affairs, there's implanted by nature the noblest and most divine of all our senses, that Conscience [sense] by which we discern what is graceful, becoming, beautiful and honourable in the affections of the soul, in our conduct of life, our words and actions. By this sense, a certain turn of mind or temper, a certain course of action, and plan of life is plainly recommended to us by nature; and the mind finds the most joyful feelings in performing and reflecting upon such offices as this sense recommends; but is uneasy and ashamed in reflecting upon a contrary course. Upon observing the like honourable actions or designs in others, we naturally favour and praise them; and have an high esteem, and goodwill, and endearment toward all in whom we discern such excellent dispositions: and condemn and detest those who take a contrary course. What is approved by this sense we count right and beautiful, and call it virtue; what is condemned, we count base and deformed and vitious.

The Forms which move our approbation are, all kind affections and purposes of action; or such propensions, abilities, or habits of mind as naturally flow from a kind temper, or are connected with it; or shew an higher taste for the more refined enjoyments, with a low regard to the meaner pleasures, or to its own interests; or lastly such dispositions as plainly exclude a narrow contracted selfishness aiming solely at its own interests or sordid pleasures. The forms disapproved are either this immoderate selfishness; or a peevish, angry, envious or ill-natured temper, leading us naturally to hurt others; or a mean selfish sensuality.

That this sense is implanted by nature, is evident from this that in all ages and nations certain tempers and actions are universally approved and their contraries condemned, even by such as have in view no interest [utility] of their own. Many artful accounts of all this as flowing from views of interest have been given by ingenious men;23 but whosoever will examine these accounts, will find that they rather afford arguments to the contrary, and lead us at last to an immediate natural principle prior to all such views.24 The agent himself perhaps may be moved by a view of advantages of any sort [by a view of more open or more hidden utility] accruing only to himself, to approve his own artful conduct; but such advantages won't engage the approbation of others (that do not gain any profit by it>: and advantages accruing to others, would never engage the agent, without a moral sense, to approve such actions. How much soever the agent may be moved by any views of his own interest [utility]; yet this when 'tis known plainly diminishes the beauty of the action, and sometimes quite destroys it. Men approve chiefly that beneficence which they deem gratuitous and disinterested; what is pretended, and yet only from views of private interest, they abhor. When the agent appears to have in view the more obvious interests of getting glory, popularity, or gainful returns, there appears little or nothing honourable. 'Tis well known that such advantages are attainable by external actions, and hypocritical shews, without any real inward goodness.

But further, does not every good action appear the more honourable and laudable the more toilsome, dangerous or expensive it was to the undertaker? 'Tis plain therefore that a virtuous course is not approved under that notion of its being profitable to the agent.25 Nor is it approved under the notion of profitable to those who approve it, for we all equally praise and admire any glorious actions of antient Heroes from which we derive no advantage, as the like done in our own times. We approve even the virtues of an enemy that are dreaded by us, and yet condemn the useful services of a Traytor, whom for our own interest we have bribed into perfidy. Nay the very Dissolute frequently dislike the vices of others which are subservient to their own.

Nor can it be alleged that the notion under which we approve actions is their tendency to obtain applause or rewards: for this consideration could recommend them only to the agent. And then, whoever expects praise must imagine that there is something in certain actions or affections, which in its own nature appears laudable or excellent both to himself and others: whoever expects rewards or returns of good offices, must acknowledge that goodness and beneficence naturally excite the love of others. None can hope for Rewards from God without owning that some actions are acceptable to God in their own nature; nor dread divine punishments except upon a supposition of a natural demerit in evil actions. When we praise the divine Laws as holy, just and good, 'tis plainly on this account, that we believe they require what is antecedently conceived as morally good, and prohibit the contrary, otherwise these Epithets would import nothing laudable.

That this sense is implanted by nature, and that thus affections and actions of themselves, and in their own nature, must appear to us right, honourable, beautiful and laudable, may appear from many of the most natural affections of the Will, both calm and passionate, which are naturally raised without any views of our own advantage, upon observing the conduct and characters and fortunes of others; and thus plainly evidence what Temper nature requires in us. Of these we shall speak presently. This moral sense diffuses it self through all conditions of life, and every part of it; and insinuates it self into all the more humane amusements and entertainments of mankind. Poetry and Rhetorick depend almost entirely upon it; as do in a great measure the arts of the Painter, Statuary, and Player. In the choice of friends, wives, comrades, it is all in all; and it even insinuates it self into our games and mirth. Whosoever weighs all these things fully will agree with Aristotle “That as the Horse is naturally fitted for swiftness, the Hound for the chace, and the Ox for the plough, so man, like a sort of mortal Deity, is fitted by nature for knowledge, and action.”

Nor need we apprehend, that according to this scheme which derives all our moral notions from a sense, implanted however in the soul and not dependent on the body, the dignity (and firmness) of virtue should be impaired. For the constitution of nature is ever stable and harmonious; nor need we fear that any change in our constitution should also change the nature of virtue, more than we should dread the dissolution of the Universe by a change of the great principle of Gravitation. Nor will it follow from this scheme, that all sorts of affections and actions were originally indifferent to the Deity, so that he could as well have made us approve the very contrary of what we now approve, by giving us senses of a contrary nature. For if God was originally omniscient, he must have foreseen, that by his implanting kind affections, in an active species capable of profiting or hurting each other, he would consult the general good of all; and that implanting contrary affections would necessarily have the contrary effect: in like manner by implanting a sense which approved all kindness and beneficence, he foresaw that all these actions would be made immediately agreeable to the agent, which also on other accounts were profitable to the system; whereas a contrary sense (whether possible or not we shall not determine,) would have made such conduct immediately pleasing, as must in other respects be hurtful both to the agent and the system. If God therefore was originally wise and good, he must necessarily have preferred the present constitution of our sense approving all kindness and beneficence, to any contrary one; and the nature of virtue is thus as immutable as the divine Wisdom and Goodness. Cast the consideration of these perfections of God out of this question, and indeed nothing would remain certain or immutable.26

XI. There are however very different degrees of approbation and condemnation, some species of virtues much more beautiful than others, and some kinds of vices much more deformed. These maxims generally hold. “Among the kind motions of the Will of equal extent, the calm and stable are more beautiful than the turbulent or passionate.” And when we compare calm affections among themselves, or the passionate among themselves, “the more extensive are the more amiable, and these most excellent which are most extensive, and pursue the greatest happiness of the whole system of sensitive nature.”27

It was already observed that our esteem of virtue in another, causes a warmer affection of good-will toward him: now as the soul can reflect on all its powers, dispositions, affections, desires, senses, and make them the objects of its contemplation; a very high relish for moral excellence, a strong desire of it, and a strong endearment of heart toward all in whom we discern eminent virtues, must it self be approved as a most virtuous disposition; nor is there any more lovely than the highest love towards the highest moral excellency.28 Since then God must appear to us as the Supreme excellence, and the inexhaustible fountain of all good, to whom mankind are indebted for innumerable benefits most gratuitously bestowed; no affection of soul can be more approved than the most ardent love and veneration toward the Deity, with a steddy purpose to obey him, since we can make no other returns, along with an humble submission and resignation of ourselves and all our interests to his will, with confidence in his goodness; and a constant purpose of imitating him as far as our weak nature is capable.

The objects of our condemnation are in like manner of different degrees. Ill-natured unkind affections and purposes are the more condemned the more stable and deliberate they are. Such as flow from any sudden passionate desire are less odious; and still more excusable are those which flow from some sudden fear or provocation. What we chiefly disapprove is that sordid selfishness which so engrosses the man as to exclude all human sentiments of kindness, and surmounts all kind affections; and disposes to any sort of injuries for one's own interests.

We justly also reckon Impiety toward God to be the greatest depravation of mind, and most unworthy of a rational Being, whether it appears in a direct contempt of the Deity; or in an entire neglect of him, so that one has no thoughts about him, no veneration, no gratitude toward him. Nor is it of any avail either to abate the moral Excellence of Piety, or the deformity of impiety, to suggest that the one cannot profit him, nor the other hurt him. For what our [conscience or moral sense] [sense of what is right and honourable] chiefly regards are the affections of the heart, and not the external effects of them. That man must be deemed corrupt and detestable who has not a grateful heart toward his benefactor, even when he can make no returns: who does not love, praise and celebrate the virtues of even good men, tho' perhaps he has it not in his power to serve or promote them. Where there is a good heart, it naturally discovers itself in such affections and expressions, whether one can profit those he esteems and loves or not. These points are manifest to the inward sense of every good man without any reasoning.

XII. This nobler sense which nature has designed to be the guide of life deserves the most careful consideration, since it is plainly the judge of the whole of life, of all the various powers, affections and designs, and naturally assumes a jurisdiction over them; pronouncing that most important sentence, that in the virtues themselves, and in a careful study of what is beautiful and honourable in manners, consists our true dignity, and natural excellence, and supreme happiness. Those who cultivate and improve this sense find that it can strengthen them to bear the greatest external evils, and voluntarily to forfeit external advantages, in adhering to their duty toward their friends, their country, or the general interest of all: and that in so doing alone it is that they can throughly approve themselves and their conduct. It likewise punishes with severe remorse and secret lashes such as disobey this natural government constituted in the soul, or omit through any fear, or any prospect of secular advantages, the Duties which it requires.

That this Divine Sense or Conscience naturally approving these more extensive affections should be the governing power in man, appears both immediately from its own nature, as we immediately feel that it naturally assumes a right of judging, approving or condemning all the various motions of the soul; as also from this that every good man applauds himself, approves entirely his own temper, and is then best pleased with himself when he restrains not only the lower sensual appetites, but even [as well as] the more sublime ones of a selfish kind [concerning his own pleasure and utility], or [but even] the more narrow and contracted affections of love toward kindred, or friends, or even his country, when they interfere with the more extensive interests of mankind, and the common prosperity of all. Our inward conscience of right and wrong [This sense] not only prefers the most diffusive goodness to all other affections of soul, whether of a selfish kind, or of narrower endearment: but also abundantly compensates all losses incurred, all pleasures sacrificed, or expences sustained on account of virtue, by a more joyful consciousness of our real goodness, and merited glory; since all these losses sustained increase the moral dignity and beauty of virtuous offices, and recommend them the more to our inward sense:* which is a circumstance peculiar to this case, nor is the like found in any other sense, when it conquers another of less power than its own. And further, whoever acts otherways cannot throughly approve himself if he examines well the inward sense of his soul: when we judge of the characters and conduct of others, we find the same sentiments of them: nay, this subordination of all to the most extensive interests is what we demand from them; nor do we ever fail in this case to condemn any contrary conduct; as in our judgments about others we are under no byass from our private passions and interests. And therefor altho' every event, disposition, or action incident to men may in a certain sense be called natural; yet such conduct alone as is approved by this diviner faculty, which is plainly destined to command the rest, can be properly called agreeable or suited to our nature.29

XIII. With this moral sense is naturally connected the others of Honour and Shame, which makes the approbations, the gratitude, and esteem of others who approve our conduct, matter of high pleasure; and their censures, and condemnation, and infamy, matter of severe uneasiness; even altho' we should have no hopes of any other advantages from their approbations, or fears of evil from their dislike. For by this sense these things are made good or evil immediately and in themselves: and hence it is that we see many solicitous about a surviving fame, without any notion [hope] that after death they shall have any sense of it, or advantage by it. Nor can it be said* that we delight in the praises of others only as they are a testimony to our virtue and confirm the good opinion we may have of our selves: for we find that the very best of mankind, who are abundantly conscious of their own virtues, and need no such confirmation, yet have pleasure in the praises they obtain.

That there's a natural sense of honour and fame30, founded indeed upon our moral sense, or presupposing it, but distinct from it and all other senses, seems manifest from that natural (motion of the soul that is called shame or) modesty, which discovers itself by the very countenance in blushing; which nature has plainly designed as a guardian not only to moral virtue, but to all decency in our whole deportment, and a watchful check upon all the motions of the lower appetites.31 And hence it is that this sense is of such importance in life, by frequently exciting men to what is honourable, and restraining them from every thing dishonourable, base, flagitious, or injurious.

In these two senses, of moral good and evil, and of honour and shame, mankind are more uniformly constituted than in the other senses; which will be manifest if the same immediate forms or species of actions be proposed to their judgment; that is, if they are considering the same affections of heart whether to be approved or condemned, they would universally agree. If indeed they have contrary opinions of happiness, or of the external means of promoting or preserving it, 'tis then no wonder, however uniform their moral senses be, that one should approve what another condemns (when they judge external actions). Or if they have contrary opinions about the divine Laws, some believing that God requires what others think he forbids, or has left indifferent; while all agree that it is our duty to obey God: or lastly, if they entertain contrary opinions about the (natural dispositions, manners, and) characters of men or parties; some believing that sect or party to be honest, pious and good, which others take to be savage or wicked. On these accounts they may have the most opposite approbations and condemnations, tho' the moral sense of them all were uniform, approving the same immediate object, to wit, the same tempers and affections.32

XIV. When by means of these senses, some objects must appear beautiful, graceful, honourable, or venerable, and others mean and shameful; should it happen that in any object there appeared a mixture of these opposite forms or qualities, there would appear also another sense, of the ridiculous [of those things that we call ridiculous or apt to excite laughter]. And whereas there's a general presumption of some dignity, prudence and wisdom in the human species; such conduct of theirs will raise laughter as shews “some mean error or mistake, which yet is not attended with grievous pain or destruction to the person”: for all such events would rather move pity. Laughter is a grateful commotion of the mind; but to be the object of laughter or mockery is universally disagreeable, and what men from their natural desire of esteem carefully avoid.

Hence arises the importance of this sense or disposition, in refining the manners of mankind, and correcting their faults. Things too of a quite different nature from any human action may occasion laughter, by exhibiting at once some venerable appearance, along with something mean and despicable. From this sense there arise agreeable and sometimes useful entertainments, grateful seasoning to conversation, and innocent amusements amidst the graver business of life.33

XV.34 These various senses men are indued with constitute a great variety of things good or evil; all which may be reduced to these three classes, the goods of the soul, the goods of the body, and the goods of fortune or external ones. The goods of the soul are ingenuity and acuteness, a tenacious memory, the sciences and arts, prudence, and all the voluntary virtues, or good dispositions of Will. The goods of the body are, perfect organs of sense, strength, sound health, swiftness, agility, beauty. External goods are liberty, honours, power, wealth. Now as all objects grateful to any sense excite desire, and their contraries raise aversion; the affections of the will, whether calm or passionate, must be equally various. We already mentioned the four general classes [calm affections] to which they may be reduced, to wit, desire, aversion, joy and sorrow: nor have we names settled to distinguish always the calm from the passionate, as there are in some other languages. The same may be said of the four turbulent motions: lust, fear, delight, and distress. But of each of these four there are many subdivisions, and very different kinds, according to the very different objects they have in view, and according as they are selfish or disinterested, respecting our own fortunes or those of others. And then among those which respect the fortunes of others there are great diversities, according to the different characters of the persons, their fortunes, and different attachments, friendships or enmities, and their various causes.

To pursue all these distinctions, and examine the several divisions made by the learned, would be tedious. We shall briefly mention the principal Passions, the names of which are also often used for the calm steddy affections of the will; nay the same name is often given to desires and joys, to aversions and sorrows.

- The several species of desire of the selfish kind respecting one's own body or fortune, are the natural appetites of food, whether plainer or more exquisite, lust, ambition, the desires of praise, of high offices, of wealth (that are called ambition and avarice). Their contraries are repelled by the aversions of fear and anger, and these of various kinds.

The goods of the soul we pursue in our desires of knowledge, and of virtue, and in emulation of worthy characters. Their contraries we avoid by the aversions of shame and modesty; we are on this subject often at a loss for appropriated names.

- The disinterested Desires respecting any sort of prosperity to others, are benevolence or good-will, parental affections, and those toward kinsmen. The affections of desire toward worthy characters, are favour or good wishes, zealous veneration, gratitude. The aversions raised by their misfortunes are fear, anger, compassion, indignation. The prosperity of bad characters moves the aversions of envy and indignation.

- The several species of Joy respecting ones own prosperous fortunes, are delectation, pride, arrogance, (pertness,) ostentation. And yet a long possession of any advantages of the body or fortune often produces satiety and disgust. From the contrary Evils arise sorrow, vexation, despair. Anger indeed by the Antients is always made a species of desire, to wit, that of punishing such as we apprehend have been injurious.

From our possessing the goods of the soul, especially virtuous affections [voluntary virtues], arise the internal joyful applauses of conscience, an honourable pride and glorying. From the contrary evils arise shame, remorse, dejection, and brokenness of spirit, which are species of sorrow.

- The virtues of others observed raise joyful love, and esteem, and veneration, and where there's intimacy, the affections of Friendship. The vices of others move a sort of sorrowful hatred, contempt or detestation. The prosperity of the virtuous, or of our benefactors, raises a joyful congratulation; their adversities raise grief, pity, and indignation. The adversities of the vitious often raise joy and triumph, and their prosperity grief and indignation.

Whoever is curious to see large catalogues of the several motions of the Will may find them in Aristotle's Ethicks, Cicero's 4th Tuscul. and Andronicus (and others>.35 But from what is above mentioned 'tis manifest that there's some natural sense of right and wrong, something in the temper and affections we naturally approve for it self, and count honourable and good; since 'tis from some such moral species or forms that many of the most natural passions arise; and opposite moral characters upon like external events raise the most opposite affections, without any regard to the private interests of the observer.

XVI. Some of these affections are so rooted in nature that no body is found without them. The appetites toward the preservation of the body are excited in every stage of life by the uneasy sensations of hunger, and thirst, and cold. The desire of offspring at a certain age, and parental affection is also universal; and in consequence of them the like affections toward kinsmen.36 The other affections when the objects are presented are equally natural, tho' not so necessary (and continuous>. The appearance of virtue in another raises love, esteem, friendship: Honourable designs are followed with favour, kind wishes, and zeal: their successes move joyful congratulation, and their disappointment sorrow and indignation; and the contrary affections attend the prosperity of the vicious, even tho' we apprehend no advantage or danger to ourselves on either side. Benefits received with a like natural force raise gratitude; and injuries, resentment and anger; and the sufferings of (others, specially of) the innocent, pity. We also justly count natural the desires of knowledge, of the several virtues, of (fame,) health, strength, beauty, pleasure, and of all such things as are grateful to any sense.37

XVII. There are some other Parts of our constitution not to be omitted, which equally relate to the understanding and will. Such as that natural disposition to associate or conjoin any ideas, or any affections, however disparate or unlike, which at once have made strong impressions on our mind; so that whensoever any occasion excites one of them, the others will also constantly attend it, and that instantly, previous to any desire. To this association is owing almost wholly our power of memory, or recalling of past events, and even the faculty of speech.38 But from such associations incautiously made we sometimes are hurt in our tempers. The meaner pleasures of sense, and the objects of our lower appetites, acquire great strength this way, when we conjoin with them some far nobler notions, tho' not naturally or necessarily allied to them, so that they cannot easily be separated. Hence by some notions of elegance, ingenuity, or finer taste, of prudence, (even of) liberality and beneficence, the luxurious ways of living obtain a much greater reputation, and seem of much more importance to happiness than they really are. Hence 'tis of high consequence in what manner the young are educated, what persons they are intimate with, and what sort of conversation they are inured to; since by all these, strong associations of ideas are formed, and the tempers often either amended or depraved.39

Of a like nature to these are Habits, for such is the nature both of the soul and body that all our powers are increased and perfected by exercise. The long or frequent enjoyment of pleasures indeed abates the keenness of our sense; and in like manner custom abates the feelings of pain.40 But the want of such gratifications or pleasures as we have long been enured to is more uneasy, and our regret the keener. And hence men are more prone to any pleasures or agreeable courses of action they are accustomed to, and cannot so easily be restrained from them.

We have already shewed that whatever is ultimately desirable must be the object of some immediate sense. But as men are naturally endued with some acuteness, forethought, memory, reason, and wisdom, they shall also naturally desire whatever appears as the proper means of obtaining what is immediately desirable; such means are riches and power, which may be subservient to all our desires whether virtuous or vitious, benevolent or malitious; and hence it is that they are so universally desired.

To finish this structure of human Nature, indued with such powers of Reason, such sublime perceptive powers, such social bonds of affection, God has also superadded the powers of speech and eloquence, by which we are capable of obtaining information of what we were ignorant of, and of communicating to others what we know: by this power we exhort, by this we persuade, by this we comfort the afflicted, and inspire courage into the fearful; by this we restrain immoderate foolish transports, by this we repress the dissolute desires and passionate resentments; this power has conjoined us in the bonds of justice and law and civil polity, this power has reclaimed Mankind from a wild and savage life.

Altho' all these several powers and faculties we have mentioned are so common to all mankind, that there are scarce any entirely deprived of any one of them; yet there is a wonderful variety of tempers: since in different persons different powers and dispositions so prevail that they determine the whole course of their lives. In many the sensual appetites prevail; in others there's an high sense of the more humane and elegant pleasures; in some the keen pursuits of knowledge, in others either ambition or anxious avarice: in others the kind affections, and compassion toward the distressed, (benevolence) and beneficence, with their constant attendants and supporters, an high sense of moral excellence and love of virtue: others are more prone to anger, envy, and the ill-natured affections.41 In the present state of mankind which we plainly see is depraved and corrupt, sensuality and mean selfish pursuits are the most universal: and those enjoyments which the higher powers recommend, the generality are but little acquainted with, or are little employed in examining or pursuing them.

This diversity of Tempers, sometimes observable from the cradle, is strangely increased by different customs, methods of education, instruction, habits, and contrary examples; not to speak of the different bodily constitutions, which belong to the art of Medicine. The same causes often concur to corrupt the manners of men, tho' our depravation in our present state cannot wholly be ascribed to them. For such is the present condition of mankind, that none seem to be born without some weaknesses or diseases of the soul, or one kind or other, tho' in different degrees. Every one finds in himself the notion of a truly good man, to which no man ever comes up in his conduct. Nay the very best of mankind must acknowledge that in innumerable instances they come short of their duty, and of that standard of moral goodness they find within them. And altho' nature has given us all some little sparks as it were to kindle up the several virtues; and sown as it were some seeds of them; yet by our own bad conduct and foolish notions we seldom suffer them to grow to maturity. (On the causes of these diseases of the soul, and on the origin of evil, various and not unlikely were the conjectures of philosophers.) But a full and certain account of the original of these disorders, and of the effectual remedies for them, in all the different degrees in which they appear in different persons, will never be given by any mortal without a divine revelation.42 And yet whosoever will set himself heartily to inquire into the true happiness of human nature, to discover the fallacious appearances of it, and to cultivate the nobler faculties of the soul, he will obtain a considerable power over the several turbulent passions, and amend or improve in a great degree his whole temper and disposition, whether it be what nature first gave him, or what his former conduct and circumstances have made it.

XVIII. The consideration of all that variety of Senses or tastes, by which such a variety of objects and actions are naturally recommended to mankind, and of a like multiplicity of natural desires; and all of them pretty inconstant and changeable, and often jarring with each other, some pursuing our own interests or pleasures of one or other of the various kinds mentioned, and some pursuing the good of others; as we have also a great many humane kind affections: This complex view, I say, must at first make human nature appear a strange chaos, or a confused combination of jarring principles, until we can discover by a closer attention, some natural connexion or order among them, some governing principles [principle] naturally fitted to regulate all the rest.43 To discover this is the main business of Moral Philosophy, and to shew how all these parts are to be ranged in order: and we shall find that with wonderful wisdom

God and kind nature has this strife composed.

Of this we may have some notion from what is above explained about that moral Power, that sense of what is becoming and honourable in our actions. Nor need we long dissertations and reasoning, since by inward reflection and examining the feelings of our hearts, we shall be convinced, that we have this moral power or Conscience distinguishing between right and wrong, plainly destined and fitted to regulate the whole of life; which clearly discovers to us that course and conduct, which alone we can entirely approve (and therefore which is most in accordance with the intention of nature>; to wit, that in which all kind affections are cultivated, and at the same time an extensive regard maintained toward the general happiness of all; so that we pursue our own interests, or those of our friends, or kinsmen, no further than the more extensive interests will allow; always maintaining sweetness of temper, kindness, and tender affections; and improving all our powers of body or mind with a view to serve God and mankind. This same moral sense also filling the soul with the most joyful satisfaction and inward applauses, and with the most cheering hopes, will strengthen it for all good offices, even tho' attended with toil and dangers, and reward our efforts with the most glorious recompense.

Nay our reason too reviewing the evidence exhibited to us in the whole order of nature, will shew us that the same course of life which contributes to the general prosperity, procures also to the agent the most stable and most worthy felicity; and generally tends to procure that competency of external things which to a good mind is in its kind the most joyful. The same reason will shew us that the world is governed by the wisest and best Providence; and hence still greater and more joyful hopes will arise. We shall thence conclude that all these practical truths discovered from reflection on our own constitution and that of Nature, have the nature and force of divine Laws pointing out what God requires of us, what is pleasing to him, and by what conduct we may obtain his approbation and favour. Hence the hopes of future happiness after death, and a strength and firmness of soul in all honourable designs. Hence the soul shall be filled with the joys of Piety and Devotion; and every good mind shall expect every thing joyful and glorious under the protection of a good Providence, not only for itself but for all good men, and for the whole universe. And when one is persuaded of these Truths, then both our social and our selfish affections will harmoniously recommend to us one and the same course of life and conduct.

Notes

[1.] This beginning on the supremacy of moral philosophy is similar to Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics (1094a) and Cicero, De finibus V.16.

[2.] This is what Cicero maintains in De Finibus V and stresses in Tusc. disp. V.

[3.] See Tusc. disp. V.19. Cicero says that, whereas for the Stoics happiness and virtue are coincident, the Stoics have different books on virtue and on the highest happiness, for logical and rhetorical reasons. Hutcheson, as well as Cicero, follows the Stoics: Hutcheson in the first two chapters of the present work, Cicero, in the fourth and fifth books of De finibus and Tusc. disp. Adding the third question: “what does it mean to follow nature” in the second edition, Hutcheson stresses his teleological and providential perspective here, as well as in many other additions. Compare the skeptical answer by Hume in his letter to Hutcheson of Sept. 17th, 1739.

[4.] This Aristotelian epistemic argument is used by Hutcheson against the legalistic perspective in ethics, that is, against those (Pufendorf, Locke and Carmichael) who base natural law on God's will or decrees.

[*] See this explained by Dr. Cumberland, de Lege Naturae. This added note shows the competence of the anonymous translator. The long chapter 2 of Cumberland's De legibus naturae is dedicated to vindicate the supremacy of man over the other animals, against Hobbes, using observations from a number of contemporary anatomists and physicians (art. 22 and ff.). Both Hutcheson and Cumberland (art. 29) drew from Cicero's remarks in De natura deorum and De legibus on the dignity of the human body.

[†] Concerning human nature, beside Aristotle's moral writings and his books on the soul, Nemesius de homine, Locke, and Malebranch; many excellent observations are made in Cicero's 5th book de finibus, Arrian, and Lord Shaftesbury's Inquiry, and Rhapsody. [Hutcheson refers to Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding, Malebranche's Recherche de la Verit&eacoute;, Arrian's The Encheiridion (“Manual”) of Epictetus, and Shaftesbury's Inquiry Concerning Virtue or Merit and The Moralists. Nemesius, bishop of Emesa in Syria at the end of the fourth century ad, is the author of De natura homine, a treatise of Christian anthropology that explains the middle position of man in the scale of beings, describes in detail the powers of the soul, and criticizes Stoic fatalism.]

[5.] See Hutcheson, Synopsis 2.1.2, p. 47.

[6.] Cf. Hutcheson, Synopsis 2.1.3, pp. 48-49.

[7.] Cf. Hutcheson, Synopsis 2.1.3, p. 51.

[8.] On pleasant, painful, or neutral sensations see Hutcheson, Synopsis 2.1.3, p. 49.

[9.] This paragraph refers to Locke, An Essay concerning Human Understanding, 2.1.3-5. Locke's distinction between external and internal sensations is different from Hutcheson's direct or antecedent and reflex or subsequent perceptions mentioned above, even if Hutcheson pretended them to be the same. Locke was mainly interested in the operations of the understanding, while Hutcheson wanted to expand on his theory of finer perceptive powers of the soul.

[10.] Cf. Hutcheson, Essay on Passions 2.1, pp. 27-28, and System 1.1.5, vol. I, pp. 8-9 and note, where Hutcheson himself refers the division to Cicero, Tusc. disp., books iii and iv.

[11.] This distinction between calm affections of the soul and vehement passions was criticized by Hume in his letter of Jan. 10th, 1743 (The letters of David Hume, edited by J. Y. T. Greig, Oxford, 1932, p. 46). Hume considered the division “vulgar and specious” (A Treatise of Human Nature, 2.1.1, p. 276 and 2.3.3), as “a calm ambition, a calm Anger . . . [which] may likewise be very strong, & have the absolute Command over the Mind” (Letters,ibidem). Hutcheson, here as well as in the Essay on Passions, follows the Cartesian, Malebranchean, and Stoic tradition.

[*] Aristotle distinguishes three kinds of appetitions in the soul: in its rational part, volition, in its irrational part, desire, and impulsiveness (De anima 432 b 5; Nichomachean ethics III 1111, b5ff.). Accordingly the schoolmen subdivide the irrational part in concupiscible and irascibile.

[12.] This sentence, added by the translator, is in square brackets in the original text. Here Hutcheson follows the Ciceronian division of the passions (Tusc. disp. IV.11-14). See also Hutcheson, Synopsis 2.1.4, p. 68, and System 1.1.5, vol. I, pp. 7-8.

[13.] Cf. An Essay on Passions 1.3, p. 13, and System 1.1.5, vol. I, p. 8.

[14.] Not a new paragraph in the Institutio, but added in the second edition.

[15.] Latin text says: “But as beside those passions or violent motions by which our self-love looks for the things which are recommended to us by a law of nature. . . .” With “particular” and “of selfish kind” the translator succeeds in making the sentence easier, but we miss the idea that particular passions are natural.

[16.] The reference to the “whole system” and to the “smaller system or party” is not in the Latin text, but is truly Hutchesonian. (See System 1.1.6, vol. I, p. 10.) In this

Online Library of Liberty: Philosophiae moralis institutio compendiaria with a Short Introduction to Moral Philosophy paragraph of the Institutio Hutcheson appears to emphasize that the desire of universal happiness is as ultimate in our nature as the desire of our own happiness. This goes against Butler's idea that virtue is coincident with calm self-love (e.g., Fifteen Sermons preached at Rolls Chapel, ii. 8. Compare System 1.7.12, vol. I, p. 139). A more polemic paragraph against Butler is found in System 1.4.12, vol. I, p. 75.

[17.] Not a new paragraph in the Institutio.

[18.] The Latin text has “judicium.” But the translator is true to Hutcheson with his “relish or sense.”

[19.] In the Institutio this paragraph is before “Whatever is grateful . . . to mankind.”

[20.] The Institutio has “sensus communis”; see the essay Sensus communis 2.3.1 and note in Shaftesbury, Characteristiks, pp. 48-49.

[*] Who in the old fable continued to live, but never awoke out of a sleep he was cast into by Diana. [See note 8 in the Institutio.]

[21.] Compare System 1.4.4, vol. I, pp. 58-59.

[22.] For the distinction between natural or involuntary virtues, like quick apprehension or memory, and voluntary or moral virtues see Cicero, De finibus, V.36. Hutcheson emphasizes the difference between natural abilities and virtues. Here, while he owns that we are naturally prompted to cultivate natural abilities and especially knowledge, as a subject fit for a book written for young students, he avoids Hume's attempt to play down the distinction in Treatise III.3.4-6. This paragraph is a precursor to the “sense of decency or dignity” described in System 1.2.7, vol. I, pp. 27-28. See below, note 34.

[23.] Literally: “Some not unlearned men want, often cunningly, these utilities to be considered or slyly forge them as the causes of our approbation and condemnation.”

[24.] The English repeatedly uses the word “interest” for the Latin “utilitas” or “utilitates.”

[25.] This and the following four sentences were added in 1745. The arguments are as old as the Inquiry on Virtue.

[26.] These last two paragraphs were added in 1745. The subjects of the last paragraph had been debated by Hutcheson in his Letters to Gilbert Burnet and resumed in his Illustrations I, pp. 233-44.

[27.] Cf. System 1.4.10, vol. I, pp. 68-69.

[28.] This sentence was criticized by Hume in his letter to Hutcheson of Jan. 10th, 1743 (pp. 46-47). Quoting from Les caractères of La Bruyère, Hume suggests that talents of body and mind are much more admired than benevolence. Again, as in his letter to Hutcheson of Sept. 17th, 1739 (p. 34), he states that Hutcheson has “limited too much” his “Ideas of Virtue” and presents this criticism as an opinion he has in common with many appraisers of his thought. Perhaps this is one of the reasons why Hutcheson repeatedly presents his catalogue of virtues in his Institutio and adds two sections.

[*]What the Author here intends is obvious, and of such importance as deserves a fuller explication. In a voluptuous life the more a man has impaired his health, his fortune, his character, or the more he has obstructed his progress in knowledge, or in the more elegant pleasures, the more also he must condemn and be dissatisfied with his own temper and conduct, and so must every observer. In the pursuits of honours and power, or the splendor of life; the more one has impaired his fortune or health, and the more of his natural pleasures and enjoyments he has sacrificed to these purposes, the more he must be dissatisfied with his own measures, and be disapproved by others. But in following the dictates of conscience, in adhering to his duty and the practice of virtue, the greater sacrifice he has made of all other enjoyments, the more he himself and all others approve his conduct and temper, and he answers the more compleatly the wishes and expectations of all who love and esteem him.

[29.] This sentence was added in 1745.

[*] This is suggested by Aristotle Ethic. ad Nicom. L. i. c. 5. [1095b, 26-30. This sentence was added in the second edition. A parallel criticism of Aristotle and the same note is found in System, vol. I, p. 26. As the note is added by the translator of the Institutio, this is evidence that he had access to a manuscript copy of the posthumous System, circulating among Hutcheson's friends since 1737.]

[30.] In this case “shame” would be a more consistent addition by the translator.

[31.] Also this sentence was added in 1745. That “pudor,” or modesty, is a natural principle connected with the sense of honour and shame is what Hutcheson debated also in System 1.5.3, vol. I, pp. 83-85.

[32.] See Inquiry on Virtue, IV, 3-5 and System 1.5.7, vol. I, pp. 92-97.

[33.] See Hutcheson, “Reflections upon Laughter,” The Dublin Weekly Journal, 5, 12, and 19 June 1725, now in Hutcheson's Collected Works, vol. 7 (New York: Garland, 1971).

[34.] This and the following section were added in the second edition. On the reasons for this addition, see the Introduction (p. ;lb;lb). This account of particular passions is different from the account given in his Essay on Passions and, in a way, new. Hutcheson bases his catalogue on the division of Cicero's four chief passions (desire and fear, joy and sorrow) (Tusc. disp. IV. 16 and ff.), but he intersects the first criterion with the division between selfish and disinterested passions and the traditional distinction between body, soul, and external goods.

[35.] Andronicus of Rhodes (First century bc) was head of the Peripatetic School and editor of Aristotle's works. A little treatise on the passions was attributed to him.

[36.] Literally: “Some of these motions arise with so natural an impulse that few are found without experience of them in some stage of life. The appetites for food, clothes, and other convenience are excited by the uneasy sensations of hunger, thirst, cold and heat. Common to every animal, at a certain age, are the desire of coupling and procreation, and a certain continuing care for the offspring.”

[37.] This second added section is more connected with the Essay on Passions 3.3-6. In this case particular passions are secondary to or dependent on the perceptions of the reflected senses.

[38.] See Synopsis 2.1.6, p. 57.

[39.] This sentence was added in 1745. If we assume that at the time Hutcheson was opposing Hume's candidature to the chair of moral philosophy in Edinburgh, the addition on the subject of the association of ideas has a certain irony since it was dangerous in Hutcheson (see Essay on Passions 4.3 and ff.), but was positively treated by Hume.

[40.] See Synopsis 2.1.8, pp. 58-59. [41.] See System 1.7.2, vol. I, p. 119.

[42.] The last seven sentences (from “The same cause often concur . . .), which were added in 1745, strengthen the moral pessimism of these paragraphs, an attitude rather unusual in Hutcheson.

[43.] Also, this paragraph was criticized by Hume in his letter to Hutcheson of Jan. 10th, 1743: he argued that Hutcheson had embraced “Dr Butler's opinion in his Sermons on Human nature; that our moral Sense has an Authority distinct from its Force and Durableness, & that because we always think it ought to prevail” (Letters, p. 47). The word for the governing self or principle suggests the influence of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, whose Meditations Hutcheson translated in 1742.