Political Economy

Spoliation by State

Is Abolition of State Possible?

Building Freedom

Anarchists have been spoken of so much lately that part of the public has at last taken to reading and discussing our doctrines. Sometimes men have even taken trouble to think, so at the present time we have at least gained the admission that anarchists do have an ideal. Their ideal is often seen as too beautiful, too lofty, for a society not composed of angels.

But is it not pretentious on my part to speak of a philosophy, when according to our critics our ideas are but dim visions of a distant future? Can anarchism pretend to possess a philosophy when it is denied that stateless capitalism has one?

This is what I am about to answer with all possible precision. I begin by taking a few elementary illustrations borrowed from natural sciences. Not for the purpose of deducing our social ideas from them - far from it; but simply the better to set off certain relations which are easier grasped in phenomena verified by the exact sciences than in examples taken only from the complex facts of human societies.

What especially strikes us at present in the sciences is the profound changes they are undergoing in their conceptions and interpretations of the facts of the universe.

There was a time when man imagined the earth placed in the center of the universe. Sun, moon, planets and stars seemed to roll round our globe; and this globe inhabited by man represented for him the center of creation. He himself - the superior being on his planet - was the elected of his Creator. The sun, the moon, the stars were made for him - towards him was directed all the attention of a God who watched the least of his actions, arrested the sun's course for him, launched his showers or his thunderbolts on fields and cities to recompense the virtue or punish the crimes of mankind. For thousands of years man thus conceived the universe.

An immense change in all conceptions of the civilized part of mankind was produced in the sixteenth century when it was demonstrated that far from being the center of the universe, the earth was only a grain of sand in the solar system - a ball much smaller even than the other planets - that the sun itself, though immense in comparison to our little earth, was but a star among many other countless stars which we see shining in the skies and swarming in the milky-way. How small man appeared in comparison to this immensity without limits, how ridiculous his pretentions! All the philosophy of that epoch, all social and religious conceptions, felt the effects of this transformation in cosmogony. Natural science, whose present development we are so proud of, only dates from that time.

But a change much more profound and with far wider-reaching results is being effected at the present time in the whole of the sciences, and anarchism is but one of the many manifestations of this evolution.

Emergent Order in Science

Take any work on astronomy of the last century. You will no longer find in it our tiny planet placed in the center of the universe. But you will meet at every step the idea of a central luminary - the sun - which by its powerful attraction governs our planetary world. From this central body radiates a force guiding the course of the planets, and maintaining the harmony of the system. Issued from a central agglomeration, planets have, so to say, budded from it. They owe their birth to this agglomeration; they owe everything to the radiant star that represents it still: the rhythm of their movements, their orbits set at wisely regulated distances, the life that animates them and adorns their surfaces. And when any perturbation disturbs their course and makes them deviate from their orbits, the central body re-establishes order in the system; it assures and perpetuates its existence.

This conception, however, is also disappearing as the other one did. After having fixed all their attention on the sun and the large planets, astronomers are beginning to study now the infinitely small ones that people the universe. And they discover that the interplanetary and interstellar spaces are peopled and crossed in all imaginable directions by little swarms of matter, invisible, infinitely small when taken separately, but all-powerful in their numbers.

It is to these infinitely tiny bodies that dash through space in all directions with giddy swiftness, that clash with one another, agglomerate, disintegrate, everywhere and always, it is to them that today astronomers look for an explanation of the origin of our solar system, the movements that animate its parts, and the harmony of their whole. Yet another step, and soon universal gravitation itself will be but the result of all the disordered and incoherent movements of these infinitely small bodies - of oscillations of atoms that manifest themselves in all possible directions. Thus the center, the origin of force, formerly transferred from the earth to the sun, now turns out to be scattered and disseminated. It is everywhere and nowhere. With the astronomer, we perceive that solar systems are the work of infinitely small bodies; that the power which was supposed to govern the system is itself but the result of the collision among those infinitely tiny clusters of matter, that the harmony of stellar systems is harmony only because it is an adaptation, a resultant of all these numberless movements uniting, completing, equilibrating one another.

The whole aspect of the universe changes with this new conception. The idea of force governing the world, pre-established law, preconceived harmony, disappears to make room for the harmony that Fourier had caught a glimpse of: the one which results from the disorderly and incoherent movements of numberless hosts of matter, each of which goes its own way and all of which hold each in equilibrium.

If it were only astronomy that were undergoing this change! But no; the same modification takes place in the philosophy of all sciences without exception; those which study nature as well as those which study human relations. In physical sciences, the entities of heat, magnetism, and electricity disappear. When a physicist speaks today of a heated or electrified body, he no longer sees an inanimate mass, to which an unknown force should be added. He strives to recognize in this body and in the surrounding space, the course, the vibrations of infinitely small atoms which dash in all directions, vibrate, move, live, and by their vibrations, their shocks, their life, produce the phenomena of heat, light, magnetism or electricity.

In sciences that treat of organic life, the notion of species and its variations is being substituted by a notion of the variations of the individual. The botanist and zoologist study the individual - his life, his adaptations to his surroundings. Changes produced in him by the action of drought or damp, heat or cold, abundance or poverty of nourishment, of his more or less sensitiveness to the action of exterior surroundings will originate species; and the variations of species are now for the biologist but resultants - a given sum of variations that have been produced in each individual separately. A species will be what the individuals are, each undergoing numberless influences from the surroundings in which they live, and to which they correspond each in his own way. And when a physiologist speaks now of the life of a plant or of an animal, he sees an agglomeration, a colony of millions of separate individuals rather than a personality, one and invisible. He speaks of a federation of digestive, sensual, nervous organs, all very intimately connected with one another, each feeling the consequence of the well-being or indisposition of each, but each living its own life. Each organ, each part of an organ in its turn is composed of independent cellules which associate to struggle against conditions unfavorable to their existence. The individual is quite a world of federations, a whole universe in himself.

And in this world of aggregated beings the physiologist sees the autonomous cells of blood, of the tissues, of the nerve-centers; he recognizes the millions of white corpuscles who wend their way to the parts of the body infected by microbes in order to give battle to the invaders. More than that: in each microscopic cell he discovers today a world of autonomous organisms, each of which lives its own life, looks for well-being for itself and attains it by grouping and associating itself with others. In short, each individual is a cosmos of organs, each organ is a cosmos of cells, each cell is a cosmos of infinitely small ones. And in this complex world, the well-being of the whole depends entirely on the sum of well-being enjoyed by each of the least microscopic particles of organized matter. A whole revolution is thus produced in the philosophy of life.

But it is especially in psychology that this revolution leads to consequences of great importance. Quite recently the psychologist spoke of man as an entire being, one and indivisible. Remaining faithful to religious tradition, he used to class men as good and bad, intelligent and stupid, egotists and altruists. Even with materialists of the eighteenth century, the idea of a soul, of an indivisible entity, was still upheld.

But what would we think today of a psychologist who would still speak like this! The modern psychologist sees in a man a multitude of separate faculties, autonomous tendencies, equal among themselves, performing their functions independently, balancing, opposing one another continually. Taken as a whole, man is nothing but a resultant, always changeable, of all his divers faculties, of all his autonomous tendencies, of brain cells and nerve centers. All are related so closely to one another that they each react on all the others, but they lead their own life without being subordinated to a central organ - the soul.

Without entering into further details you thus see that a profound modification is being produced at this moment in the whole of natural sciences. Not that this analysis is extended to details formerly neglected. No! the facts are not new, but the way of looking at them is in course of evolution. And if we had to characterize this tendency in a few words, we might say that if formerly science strove to study the results and the great sums (integrals, as mathematicians say), today it strives to study the infinitely small ones - the individuals of which those sums are composed and in which it now recognizes independence and individuality at the same time as this intimate aggregation.

As to the harmony that the human mind discovers in nature, and which harmony is on the whole but the verification of a certain stability of phenomena, the modern man of science no doubt recognizes it more than ever. But he no longer tries to explain it by the action of laws conceived according to a certain plan pre-established by an intelligent will.

What used to be called "natural law" is nothing but a certain relation among phenomena which we dimly see, and each "law" takes a temporary character of causality; that is to say: If such a phenomenon is produced under such conditions, such another phenomenon will follow. No law placed outside the phenomena: each phenomenon governs that which follows it - not law.

Nothing preconceived in what we call harmony in Nature. The chance of collisions and encounters has sufficed to establish it. Such a phenomenon will last for centuries because the adaptation, the equilibrium it represents has taken centuries to be established; while such another will last but an instant if that form of momentary equilibrium was born in an instant. If the planets of our solar system do not collide with one another and do not destroy one another every day, if they last millions of years, it is because they represent an equilibrium that has taken millions of centuries to establish as a resultant of millions of blind forces. If continents are not continually destroyed by volcanic shocks it is because they have taken thousands and thousands of centuries to build up, molecule by molecule, and to take their present shape. But lightning will only last an instant; because it represents a momentary rupture of the equilibrium, a sudden redistribution of force.

Harmony thus appears as a temporary adjustment established among all forces acting upon a given spot - a provisory adaptation. And that adjustment will only last under one condition: that of being continually modified; of representing every moment the resultant of all conflicting actions. Let but one of those forces be hampered in its action for some time and harmony disappears. Force will accumulate its effect, it must come to light, it must exercise its action, and if other forces hinder its manifestation it will not be annihilated by that, but will end by upsetting the present adjustment, by destroying harmony, in order to find a new form of equilibrium and to work to form a new adaptation. Such is the eruption of a volcano, whose imprisoned force ends by breaking the petrified lavas which hindered them to pour forth the gases, the molten lavas, and the incandescent ashes.

Such, also, are the revolutions of mankind.

An analogous transformation is being produced at the same time in the sciences that treat of man. Thus we see that history, after having been the history of kingdoms, tends to become the history of nations and then the study of individuals. The historian wants to know how the members, of which such a nation was composed, lived at such a time, what their beliefs were, their means of existence, what ideal of society was visible to them, and what means they possessed to march towards this ideal. And by the action of all those forces, formerly neglected, he interprets the great historical phenomena.

So the man of science who studies jurisprudence is no longer content with such or such a code. Like the ethnologist he wants to know the genesis of the institutions that succeed one another; he follows their evolution through ages, and in this study he applies himself far less to written law than to local customs - to the "customary law" in which the constructive genius of the unknown masses has found expression in all times. A wholly new science is being elaborated in this direction and promises to upset established conceptions we learned at school, succeeding in interpreting history in the same manner as natural sciences interpret the phenomena of nature.

Political Economy

And, finally, political economy, which was at the beginning a study of the wealth of nations, becomes today a study of the wealth of individuals. It cares less to know if such a nation has or has not a large foreign trade; it wants to be assured that bread is not wanting in the peasant's or worker's cottage. It knocks at all doors - at that of the palace as well as that of the hovel - and asks the rich as well as the poor: What are the barriers to getting your needs satisfied, both for necessities and luxuries?

And as it discovers that the most pressing needs of nine-tenths of each nation are not satisfied, it asks itself the question that a physiologist would ask himself about a plant or an animal: - "Which are the means to satisfy the needs of people with the least loss of freedom? What type of social arrangements and norms guarantee to each, and consequently to all, a reasonable chance to live their own vision of a good life?" It is in this direction that economic science is being transformed; and after having been so long perverted to a simple statement of the interests of a ruling caste, it is now finally becoming a science in the true sense of the word - a physiology of human societies.

While our new philosophy of anarchism is being worked out, we may observe that it posits very a different conception of society from that which now prevails. Under the name of anarchism, a new interpretation of the past and present life of society arises, giving us at the same time a forecast as regards its future, analogous to the above mentioned revolution in the natural sciences. Anarchism, therefore, appears as a constituent part of modern science and philosophy, which is why anarchists come in contact on so many points with the greatest thinkers, poets, and scientists.

In fact it is certain that as the human mind frees itself from ideas inculcated by minorities of rulers, priests, and military chiefs, all striving to establish their domination, and of crony scientists and "intellectuals" paid to perpetuate it, a conception of society is arising in which there is no longer room for those oppressive minorities. Anarchists envision a society which has possession of the "gratuitous domain" of knowledge and social capital accumulated by preceding generations, organizing itself so as to make use of this capital through free production and trade and respect for property rights, and constituting itself without recreating the power of the ruling minorities, the institution of State.

Anarchism incorporates an infinite variety of capacities, temperaments and individual energies: it excludes none. It even calls for struggles and contentions; because we know that periods of contests, so long as they were freely fought out without the weight of constituted authority being thrown on one side of the balance, were periods when human genius took its mightiest flights and achieved the greatest aims. Acknowledging, as a fact, the equal rights of its members to the non-rivalrous treasures accumulated in the past - the gratuitous domain - it no longer recognizes a division between exploited and exploiters, governed and governors, dominated and dominators.

Anarchism seeks to establish a harmonious compatibility in its midst - not by subjecting all its members to an authority that is fictitiously supposed to represent society, not by trying to establish uniformity, but by urging all men to develop free initiative, free action, free association.

It seeks the most complete development of individuality combined with the highest development of voluntary association in all its aspects, in all possible degrees, for all imaginable aims; ever changing, ever modified associations which carry in themselves the elements of their durability and constantly assume new forms which answer best to the multiple aspirations of all. Thus, anarchism as such does not favor capitalist private property, nor communist collective property, but leaves such norms up to local communities and individual choice. Declaring that there is one true property system is every bit as irrational as declaring that we already know everything about astronomy or geology.

Anarchism favors a society to which pre-established forms, crystallized by law, are repugnant; which looks for harmony in an ever-changing and fugitive equilibrium between a multitude of varied forces and influences of every kind, following their own course, - these forces themselves promoting the energies which are favorable to their march towards progress, towards the liberty of developing in broad daylight and counterbalancing one another.

This conception and ideal of society is certainly not new. On the contrary, when we analyze the history of popular institutions - the family, the clan, the village community, and even urban communities - we find the same popular tendency to constitute a society according to this idea of liberty; a tendency, however, always trammelled by domineering minorities. All popular movements bore this stamp more or less, and with the Anabaptists and their forerunners in the ninth century we already find the same ideas clearly expressed in the religious language which was in use at that time. Unfortunately, till the end of the last century, this ideal was always tainted by a theocratic spirit. It is only nowadays that the conception of society deduced from the observation of social phenomena is rid of its theistic swaddling-clothes.

It is only today that the ideal of a society where each governs himself according to his own will (which is evidently a result of the social influences borne by each) is affirmed in its economic, political and moral aspects at one and the same time, and that this ideal presents itself based on the necessity of eliminating or greatly reducing compulsory government. Those that try to enforce their preferred economic system are every bit as statist as those who force conscription or taxation upon others. The goal is to eliminate the State, not to promote one's favorite flavor of property.

We know full well that it is futile to speak of liberty as long as taxation and compulsory government still exist.

"Speak not of liberty - poverty is slavery!" is a perverse formula, since it ignores the difference between natural scarcity and man-imposed aggression. Unfortunately, the obscene notion that robbing one's fellow man is necessary or good for society has penetrated into the ideas of the great working-class masses and filters through all the present literature.

Millions of anarchists of both hemispheres and all types, from anarcho-capitalist to anarcho-communist, already agree that the present form of corporatist appropriation cannot last much longer. Even the crony capitalist cohorts of rulers realize that their fascism must end soon, so they dare not defend it with their former assurance. Their only argument is reduced to saying to us: "I have my moated mansion. I can live through the reset, no problem!" But as to denying the fatal consequences of the present government control over property, capital, and production, they cannot do it. It takes an anarcho-capitalist to justify the morality of the entitlement theory of justice. For statists and their retinue, property is merely a matter of "might makes right," and the ruling caste currently has the might to rob people.

Spoliation by State

The ruling elites always claim that, without their wise rule, people would be unable to survive. Such a fiction can be kept up for some time by propaganda and goverment schooling. The great majority of people may not even reflect about it; but from the moment a minority of thinking men agitate the question and submit it to all, there can be no doubt of the result. Popular opinion answers: "It is by spoliation and collusion with the State that crony capitalists gain and hold their wealth!"

Likewise, how can the peasant be made to believe that the bourgeois or manorial land belongs to the proprietor who has a legal claim by virtue of conquest, when a peasant can tell us the history of each bit of land and how it was originally homesteaded? Above all, how make him believe that it is useful for the nation that Mr. CronyCap steals a piece of land for himself while using the government "gun" to confiscate and rezone it to his advantage?

And, lastly, how make the worker in a factory, or the miner in a mine, believe that factory and mine equitably belong to their present masters, when worker and even miner are beginning to see clearly through scandal, bribery, pillage of the State and the legal theft, from which great commercial and industrial property are derived? Rational resource usage is based on the entitlement theory of justice, not the whims of rulers and their cohorts.

But a greater evil of the present system becomes more and more marked; namely, the belief in the "capitalism concentrates wealth" myth. This is the empirically and logically false belief that, in a system based on private property, all that is necessary to life and to production - land, housing, food and tools - will necessarily pass into the hands of a few, and the production of necessities that would give well-being to all is continually hampered. In fact, capitalist production has been a boon for workers and people in general. Poverty has gone from over 95% of humanity to less than 10% since the industrial revolution, and that is despite the predation of State. People generally perceive how the corporatist system and the State hinder their well-being in every way.

The very essence of the present economic system is that people can never fully enjoy the well-being he and others have produced, since the ruling caste - those who live at his expense - will always steal a significant proportion of his productivity. The more a government is advanced in spoliation technology, the greater the theft. Inevitably, industry is directed by incompetent rulers or their flunkies, and will have to be directed, not towards efficiency, but towards that which brings the greatest temporary profit to a few cronies of the rulers. Of necessity, the abundance of the ruling caste will be supported by the theft of others.

We have already obtained the unanimous assent of those who have studied the subject, that a society, once having achieved liberty and property rights for all, can liberally assure abundance to nearly everyone willing to work a bit - for four or five hours effective and manual work a day, as far as regards production. If everyone, from childhood, learned whence came the bread he eats, the house he dwells in, the book he studies, and so on; and if each one understood simple economics, the division of labor, and the role of property norms, then society would be more prosperous and justice would prevail.

Is Abolition of State Possible?

There is no longer any doubt as regards the possibility of wealth in a stateless society, armed with our present machinery and tools. Doubts only arise when the question at issue is whether a society can exist in which man's actions are not subject to State control; whether, to reach well-being, it is necessary for communities to sacrifice the personal liberty they have recovered from the State? Anarchists believe that only by the abolition of the State, by attainment of perfect liberty by the individual, by free agreement, association, and absolute free trade, we can achieve the liberty of mankind.

That is the question outweighing all others at present, and anarchism must solve it, on pain of seeing all its efforts endangered and all its ulterior development paralyzed. Let us, therefore, analyze it with all the attention it deserves.

If every anarchist will carry his thoughts back to an earlier date, he will no doubt remember the host of prejudices aroused in him when, for the first time, he came to the conclusion that abolishing compulsory government has become an historical necessity. The same feelings are today produced in any man who for the first time hears that the abolition of the State, its laws, its entire system of management, governmentalism and centralization, had become a historical necessity: that the abolition of corporatism without the abolition of the State is materially impossible. Our whole education - made, be it noted, by State, in the interests of rulers - revolts at this conception. It is it less true for that? Shall we allow our belief in the State to make us slaves?

To begin with, if man, since his origin, has always lived in societies, the State is but one of the forms of social life, quite recent as far as regards European societies. Men lived thousands of years before the first States were constituted; Greece and Rome existed for centuries before the Macedonian and Roman Empires were built up, and for us modern Europeans the centralized States date but from the sixteenth century. It was only after the gunpowder weapons and the printing press were invented and perfected circa 1500 that the authority of the immortal corporate State could be fully established. The return on brute force rose, with the rulers' ability to teach serfs a common language and hand them a musket. Now we have computers and strong cryptography, so the tide has turned. Now the return on brute force is falling fast. All the tanks and nuclear bombs on earth can't break PGP.

We know well the means by which this association of lord, priest, merchant, judge, soldier, and king founded its domination. It was by the use of firearms and propaganda, and the prohibition of property rights for anyone but the ruling caste. Objective property rights, based on homesteading, voluntary trade, and rectification of unjust transactions, are never upheld by rulers, since their very purpose is to sustainably plunder the general population.

It is only recently that we began to reconquer, by struggle, by revolt, the first steps of the right of association that was freely practised by the artisans and the tillers of the soil through the whole of the middle ages.

And, already now, the earth is covered by thousands of voluntary associations (businesses, firms, clubs, etc.) for study and teaching, for industry, commerce, science, art, literature, exploitation, resistance to exploitation, amusement, serious work, gratification and self-denial, for all that makes up the life of an active and thinking being. We see these societies rising in all nooks and corners of all domains: political, economic, artistic, intellectual. Some are as shortlived as roses, some hold their own for several decades, and all strive - while maintaining the independence of each group, circle, branch, or section - to promote the goals of their particular association.

These agorist individuals and firms have already begin to replace the functions of the State, and strive to substitute free action of volunteers for that of a centralized State. We see insurance companies and private defense agencies arise against theft; societies for coast defense, volunteer societies for land defense, which the State endeavors to get under its thumb, thereby making them instruments of domination, although their original aim was to do without the State. Were it not for State, voluntary associations would have already conquered the whole of the immense domain of education. And, in spite of all difficulties (and the assistance of coronavirus), they begin to invade this domain as well, and make their influence felt.

And when we mark the progress already accomplished in that direction, in spite of and against the State, which tries by all means to maintain its supremacy of recent origin; when we see how voluntary societies invade everything and are only impeded in their development by the State, we are forced to recognize a powerful tendency, a latent force in modern society. And we ask ourselves this question: If five, ten, or twenty years hence - it matters little - people succeed by agorism in destroying the government-supported cartels of bankers, police, judges, and soldiers; if the people become masters of their destiny for a few months, and are allowed to keep the wealth they have created and which belong to them by right - will they really begin to reconstitute that blood-sucker, the State? Or will they not rather try to organize from the simple to the complex according to mutual agreement and to the infinitely varied, ever-changing needs of each locality, utilizing the freed market to secure prosperity for themselves?

Will they follow the dominant tendency of the century, towards decentralization, home rule and free agreement; or will they march contrary to this tendency and strive to reconstitute demolished authority?

Foolish men tremble at the idea that society might be without judges or police in an anarchist society. But that is not at all what anarchists want, and is a major misunderstanding. Anarchists do not want to abolish judges and police; we want free competition and individual choice in which judges and police we associate ourselves with.

When we ask for the abolition of the State and its coercive organs, we are always told that we dream of a society composed of men better than they are in reality. But no; a thousand times, no. All we ask is that men should not be made worse than they are, by such institutions, and that there be no monopolies!

It is often said that anarchists live in a world of dreams to come, and do not see the things which happen today. We see them only too well, and in their true colors, and that is what makes us carry the hatchet into the forest of prejudices that besets us.

Far from living in a world of visions and imagining men better than they are, we see them as they are; and that is why we affirm that the best of men is made essentially bad by the exercise of authority, and that the theory of the "balancing of powers" and "control of authorities" is a hypocritical formula, invented by those who have seized power, to make the "sovereign people," whom they despise, believe that the people themselves are governing. It is because we know men that we say to those who imagine that men would devour one another without those governors: "You reason like the king, who, being sent across the frontier, called out, 'What will become of my poor subjects without me?'."

Ah, if men were those superior beings that the utopians of authority like to speak to us of, if we could close our eyes to reality and live like them in a world of dreams and illusions as to the superiority of those who think themselves called to power, perhaps we also should do like them; perhaps we also should believe in the virtues of those who govern.

If the gentlemen in power were really so intelligent and so devoted to the public cause, as panegyrists of authority love to represent, what a pretty government and paternal utopia we should be able to construct! The employer would never be the tyrant of the worker; he would be the father! The factory would be a palace of delight, and never would masses of workers be doomed to physical deterioration. A judge would not have the ferocity to condemn the wife and children of the one whom he sends to prison to suffer years of hunger and misery and to die some day of anemia; never would a public prosecutor ask for the head of the accused for the unique pleasure of showing off his oratorical talent; and nowhere would we find a jailer or an executioner to do the bidding of judges who have not the courage to carry out their sentences themselves.

Oh, the beautiful utopia, the lovely Christmas dream we can make as soon as we admit that those who govern represent a superior caste, and have hardly any or no knowledge of simple mortals' weaknesses! It would then suffice to make them control one another in hierarchical fashion, to let them exchange fifty papers, at most, among different administrators, when the wind blows down a tree on the national road. Or, if need be, they would have only to be valued at their proper worth, during elections, by those same masses of mortals which are supposed to be endowed with all stupidity in their mutual relations but become wisdom itself when they have to elect their masters.

All the science of government, imagined by those who govern, is imbibed with these utopias. But we know men too well to dream such dreams. We have not two measures for the virtues of the governed and those of the governors; we know that we ourselves are not without faults and that the best of us would soon be corrupted by the exercise of power. We take men for what they are worth, - and that is why we hate the government of man by man, and why we work with all our might - perhaps not strong enough - to put an end to it.

Building Freedom

But it is not enough to destroy. We must also know how to build, and it is owing to not having thought about it that the masses have always been led astray in all their revolutions. They did not realize that true revolution is in the mind and in the social infrastructure. Agorism, building alternatives to services the State tries to provide and monopolize, is necessary for any revolution to be successful and permanent. Braindead destruction merely allows a new ruling caste to emerge.

That is why anarchism, when it works to destroy authority in all its aspects, when it demands the abrogation of decreed laws and the abolition of the mechanism that serves to impose them, when it refuses all coercive organization and preaches free agreement, at the same time strives to maintain and enlarge the precious kernel of social norms and infrastructure for liberty, without which no human or animal society can exist. Only instead of demanding that those social customs should be maintained through the authority of a few, it demands it from the continued voluntary consent of all participants.

Anarchist values and institutions are of absolute necessity for society, not only to solve economic difficulties, but also to maintain and develop social norms that allow men peaceful interactions with one another.

In fact when we ask ourselves by what means a certain moral level can be maintained in a human or animal society, we find only three such means: the repression of anti-social acts; moral teaching; and the practice of mutual help, also known as free enterprise, itself. And as all three have already been put to the test of practice, we can judge them by their effects.

As to the impotence of repression - it is sufficiently demonstrated by the disorder of present society. In the domain of economy, coercion has led us to corporatism; in the domain of politics to the State; that is to say, to the destruction of all natural and consensual ties that formerly existed among citizens. A nation, perverted by statism, becomes nothing but an incoherent mass of obedient subjects of a central authority.

Practised for centuries, repression has worked so badly that it has but led us into a blind alley from which we can only escape by taking a hatchet to the evil institution of State.

Far be it from us not to recognize the importance of the second factor, moral teaching - especially that which is unconsciously transmitted in society and results from the whole of the ideas and comments emitted by each of us on facts and events of everyday life. But this force can only act on society under one condition, that of not being bamboozled by a mass of contradictory immoral teachings spewing from government education, indoctrination, and propaganda.

The third element alone remains - the institution itself, acting in such a way as to make social acts a state of habit and instinct. This element - history proves it - has never missed its aim, never has it acted as a double-bladed sword; and its influence has only been weakened when custom strove to become immovable, crystallized to become in its turn a religion not to be questioned, when it endeavored to absorb the individual, taking all freedom of action from him and compelling him to revolt against that which had become, through its crystallization, an enemy to progress.

In fact, all that was an element of progress in the past or an instrument of moral and intellectual improvement of the human race is due to the practice of free enterprise, to the customs that recognized the rights of men and brought them to ally, to unite, when necessary, for the purpose of producing and consuming, to unite for purposes of defense, to federate and to recognize no other judges in fighting out their differences than the arbitrators they took from their own midst.

Each time these institutions, issued from popular genius, when it had reconquered its liberty for a moment, - each time these institutions developed in a new direction, the moral level of society, its material well-being, its liberty, its intellectual progress, and the affirmation of individual originality made a step in advance. And, on the contrary, each time that in the course of history, whether following upon a foreign conquest, or whether by developing authoritarian prejudices, men become more and more divided into governors and governed, exploiters and exploited, the moral level fell, the well-being of the masses decreased in order to insure riches to a few, and the spirit of the age declined.

History teaches us this, and from this lesson we have learned to have confidence in free capitalist institutions to raise the moral level of societies, formerly debased by the practice of authority.

Today we live side by side without knowing one another. We come together at meetings on an election day: we listen to the lying or fanciful professions of faith of a candidate, and we return home. The State has the care of all questions of public interest; the State alone has the function of seeing that we do not harm the interests of our neighbor, and, if fails in this, of punishing us in order to repair the evil.

Our neighbor may die of hunger or murder his children, is no business of ours; it is the business of the policeman. You hardly know one another, nothing unites you, everything tends to alienate you from one another, and finding better way, you ask the Almighty (formerly it was and, now it is the State) to do all that lies within his power to stop anti-social passions from reaching their highest climax.

In an anarchist society such subservience to an outside force could not exist. Anarchist organizations are not constructed by legislative fiat. They are the result of free choices by all participants, a natural growth, a product of the constructive genius of individuals. Anarchism cannot be imposed from above, by definition. It must be free.

It cannot exist without creating a continual contact between all for the thousands and thousands of common transactions - this is called the division of labor and is a boon to prosperity. It cannot exist without creating local life, independent in the smallest unities - the block of houses, the street, the district, the town. It would not answer its purpose if it did not cover society with a network of thousands of associations to satisfy its thousand needs: the necessaries life, articles of luxury, of study, enjoyment, amusements. This is called a free market. And such associations may not remain narrow and local; they may tend (as is already the case with learned societies, computer clubs, humanitarian societies and the like) to become international.

And the sociable customs that anarchism - even if only partial at first - must inevitably engender in life would already be a force incomparably more powerful than the State's repressive machinery.

This, then, is the form - sociable institution - of which we ask the development of the spirit of harmony that the State has undertaken to impose on us. These remarks contain our answer to those who affirm that capitalism and anarchism cannot go together. They are, you see, a necessary complement to one another. The most powerful development of individuality, of individual originality - as one of our luminaries has so well said, - can only be produced when the fundamental conditions of liberty are satisfied; when the struggle for existence against the violent and aggressive forces of State has been won; when man's productivity is no longer stolen by ruling looters - then only, his intelligence, his artistic taste, his inventive spirit, his genius, can develop freely and ever strive to greater achievements.

Anarchism is the best basis for individual development and freedom. Individual liberty is the only strategy known which promotes the full expansion of man's faculties, the superior development of what is original in him, the greatest fruitfulness of intelligence, feeling and will. Such being our ideal, what does it matter to us that it cannot be realized at once!

Our first duty is to find out by an analysis of society, its characteristic tendencies at a given moment of evolution and to state them clearly. Then, to act according to those tendencies in our relations with all those who think as we do. And, finally, from today and especially during the transition period, to work for the destruction of statist institutions, as well as the prejudices and attitudes that promote State oppression. That is all we can do by peaceable agorist methods, and we know that by favoring those tendencies we contribute to progress, while those who resist them impede the march of progress.

Nevertheless men often speak of stages to be travelled through, and they propose to work to reach what they consider to be the nearest station and only then to take the high road leading to what they recognize to be a still higher ideal.

But reasoning like this seems to me to misunderstand the true character of human progress and to make use of a badly chosen military comparison. Humanity is not a rolling ball, nor even a marching column. It is a whole that evolves simultaneously in the multitude of millions of which it is composed. And if you wish for a comparison you must rather take it in the laws of organic evolution than in those of an inorganic moving body.

The fact is that each phase of development of a society is a resultant of all the activities of the intellects which compose that society; it bears the imprint of all those millions of wills. Consequently whatever may be the stage of development that the twenty-first century is preparing for us, this future state of society will show the effects of the awakening of libertarian ideas which is now taking place. And the depth with which this movement will be impressed upon twenty-first century institutions will depend on the number of men who will have broken today with authoritarian prejudices, on the energy they will have used in attacking old institutions, on the impression they will make on the masses, on the clearness with which the ideal of a free society will been impressed on the minds of people.

Some will know how to rouse the spirit of initiative in individuals and in groups, those who will be able to create in their mutual relations a movement and a life based on the principles of voluntaryism and free understanding - those that will understand that variety, conflict even, is life and that uniformity is death, - they will work, not for future centuries, but in good earnest for the next revolution, for our own times.

We need not fear the dangers and "abuses" of liberty. It is only those who do nothing who make no mistakes. As to those who only know how to obey, they make just as many, and more mistakes than those who strike out their own path in trying to act in the direction their intelligence and their social education suggest to them.

The only thing to be done when we see anti-social acts committed in the name of liberty of the individual, is to have the courage to say aloud in anyone's presence what we think of such acts. This can perhaps bring about a conflict; but conflict is life itself. And from the conflict will arise an appreciation of those acts far more just than all those appreciations which could have been produced under the influence of established authoritarian ideas.

It is evident that so profound a revolution producing itself in people's minds cannot be confined to the domain of ideas without expanding to the sphere of action.

If you want that absolute liberty of the individual, and consequently, his life be respected, you must necessarily repudiate the government of man by man, whatever shape it assumes. You are logically compelled to accept the principles of anarchism.

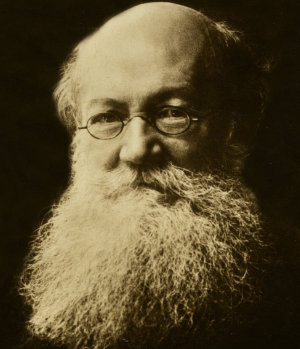

* Terp Krokinpot is an anagram of Petr Kropotkin. This piece is Hogeye Bill's rendition of what Kropotkin would have written in his essay of the same name had he been educated in modern STV economics, rather than been perverted by the socialist exploitation theory.