Rights

Aggression

Property

Entitlement

Just Acquisition

Objective Morality

Fraud

Compensation

Threats

Force in Defense

Accidents

Notes

Libertarianism is the philosophy, the how and why, of human freedom. Libertarianism is based on a single principle, called the Non-Aggression Principle, or commonly, the NAP. The NAP states that no person has the right to aggress against the property of others. That seems pretty simple and uncontroversial at first glance, but it can get difficult.

Because the point is to fully understand what this principle means, there are terms that need to be defined. Specifically, the words "right," "aggress," and "property." All of the following concepts tie in to each other, so one has to take the information as it comes and, hopefully, by the end, it will be clear.

Rights

Rights is a word that gets tossed around a lot without any explanation of what it means. People can mean many different things when they use this word, but this is what it means to libertarians: a right is an entitlement to one's property. In the context of the NAP, we can say, "because no one is entitled to the property of others and everyone is entitled to their own property, no one may morally interfere with the entitlement others have to their property."1 The problem here, as you may have noticed, is that by defining rights in the context of the NAP, we're further away from understanding the NAP than it appears we were before. Now the questions are not only of defining the words "right," "aggress," and "property," but what is entitlement? How do libertarians define morality?

We need to take these step by step, so let's continue with the current mission of defining "right," "aggress," and "property."

Aggression

We've opened a can of worms by defining rights, which we'll return to later. Now, let's define "aggression" and open another can. In the context of libertarianism, aggression is the violation of the property of others. Ignore, for now, that we haven't defined property yet. For example, assume, for the sake of simplicity, that a person's body is considered their property. Two men are arguing. One of the men loses control and physically engages his opponent by striking him. This man has violated the property of his opponent because he has interfered in his opponent's entitlement to his property, namely, his body. Here is the modified version of the NAP again, now that we understand what aggression is; "because no one is entitled to the property of others and everyone is entitled to their own property, no one may morally interfere with the entitlement of others to their property." For the sake of clarity, reactionary force, or defensive force, is not considered aggression and we will address this concept later.

Now, after defining aggression, we have added even more questions than we had after defining rights, like, “what about threats or fraud.” We'll have to come back to those questions after we define property.

Property

When libertarians refer to property, they are referencing those material objects to which no one else has an equal or greater claim, nor for which others can be assigned responsibility. For example, everyone has a “self” consisting of a body and mind. The self is non-transferable, meaning that one cannot give away or sell or in any other manner divest the self (in this way, not only does no one have an equal or higher claim, but no others have any claim at all). The self cannot be given, in any manner, to someone else. That's not to say that it should or shouldn't be transferred to others, but that transfer is impossible. The self was never in the possession of another and never can be in the possession of another. Therefore, no one has a higher claim to the self and its constituent parts than the person manifested by the self. Responsibility for the consequences of the actions of a person cannot be assigned to others precisely because the self cannot be controlled by others.2 If Tom does harm to Bob, Tom is responsible because he used his property, to which no one has an equal or higher claim to harm Bob. In fact, no one has any claim to Tom's self and, therefore, they can have no responsibility for his actions. There is no link between responsibility for Tom's actions and other people. This is the basis of property and the point at which philosophy and practicality meet.

If a person were to use their body to build a shelter, who would have an equal or greater claim to that shelter? Someone who did not build the shelter? If that shelter were built on a mountainside and it collapsed, rolled down the mountain and hurt someone below, who would be responsible for that person's injury? Someone who did not build the shelter? If those not involved in creating something have an equal or higher claim to it and can be assigned responsibility for it, then consider this: assume that others have an equal or higher claim to your body than you. If this is true, then you also have an equal or higher claim to the bodies of those who have an equal or higher claim to your body. Your property is their property and their property is your property, which effectively returns us to the original position, which is logically circular.

More clarification is warranted on this property definition. Property has been defined as material objects to which no one has an equal or higher claim. Equal? Bob and Tom pooled their resources and built a house. They agreed that they would both be 50% owners of the house. So the house is a material object to which someone has an equal or higher claim, right? No. Bob owns half of the house. Tom owns half of the house. No one has an equal or higher claim to Bob's half of the house, nor does anyone have an equal or higher claim to Tom's half of the house. That is how joint ownership fits into the property definition and clarifies the term "equal."

Now that rights, aggression, and property have been defined, the NAP can be evaluated clearly: no person has the right to aggress against the property of others. Now we can move forward to answer some of the questions brought about by defining the words above.

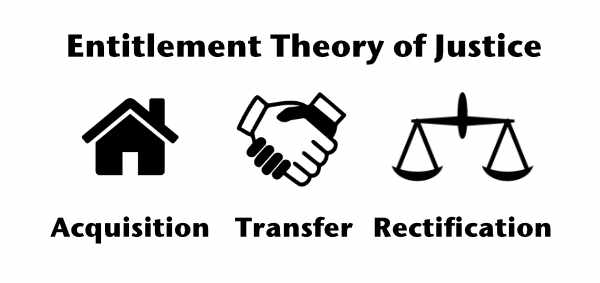

Entitlement

When defining rights, the term "entitlement" was used, but wasn't defined: "… a right is an entitlement to one's property." An entitlement is the extent to which one has a claim to a material good. A person has the full claim on his self, and, therefore, is fully entitled. In the example of Bob and Tom's house, each of them has some entitlement to the house. This term is the bridge between the inextricably linked ideas of "rights" and "property." Rights describe the entitlement of an owner to his property. An owner has the right to his property because of his entitlement. You own your property, you may employ it as you see fit and this inherent entitlement is described as a right.

Just Acquisition

How a person uses his property to create more property was explained, but what about those material objects that already exist, but have not become property? How does one acquire property from existing material objects?

Bob is flying his drone. He sees a dollar on the ground with his drone’s camera. He thinks, “Ooh, there's a dollar! I'm going to go get it!”, but before Bob arrives, Tom, who is standing right beside the dollar, and who is unaware of Bob's actions and plans, notices the dollar and picks it up. Who is the rightful owner of the dollar?

Think back to the example of the shelter on the mountainside. That shelter was the property of the owner because he employed his current property in the creation of that shelter. That gave him the highest claim to that material object (and the responsibility for it, though that isn't as significant with a dollar laying on the ground). In the case of the dollar, even though Bob has employed his drone to find it and then used his body to run over to it in order to pick it up, he hasn't used his property in the actual acquisition of the dollar. Tom, on the other hand, took similar action to Bob, using his eyes to find the dollar then using his body to bend down and reach for it. The difference between Bob and Tom is that Tom actually employed his property in the acquisition of the dollar by grasping it and lifting it. Bob did not.

This idea is similar to other ideas on property acquisition like “mixing labor”. The subtle refinement here is that it isn't labor, per se, but the employment of property that justifies acquisition. It may go without saying that existing property may be acquired through trade between owners, simply because one may transfer his property to others if he sees fit. That is his right.3

Objective Morality

Another crucial, yet undefined term in the rights definition was morality. Simply, morality is the principles involved in determining right from wrong. Controversially, there are two categories of morality: subjective and objective. Subjective, in this context, means not universally applicable, or subject to opinion. Maybe a more accurate definition is "based on individual values or preferences." To illustrate, a subjective statement might be, "chocolate ice cream is the best ice cream." That's an opinion based on one's preferences. Others may prefer different flavors. If one states that chocolate is best and another states that vanilla is best, they are both right, because their preferences only apply to themselves. One's preferences are a consequence of one's unique, inherent qualities. We are all genetically human, but those genes are expressed uniquely. Preference flows from this uniqueness as well as the available resources to achieve goals.

Objective is, obviously, the opposite of subjective. Objective means applying universally, or not subject to opinion. More accurately, "not based on individual values or preferences." An example of objectivity might be, "2+2=4." The statement "2+2=4" is mathematically provable and not subject to one's preferences or values. It is true unto itself, universally, for all people at all times. Many subjective moralities exist, maybe as many as humans exist, but one objective morality also exists.

Property is a constant among human beings. All humans own property: their selves. Of course, this isn't the only property people own, but it is the only property that everyone owns.

As explained previously, all owners are entitled to their property and, by the nature of property, no others have an entitlement to one's property. Therefore, only an owner (he who is entitled to property) may make decisions about the use of his property. Making decisions about property use is not an issue until other people are involved. When people interact, property, being a constant among all humans, is subject to those interactions.

Morality comes into play because interaction with the property of others can result in the violation of an owner's entitlement. For example, your bike is your property. If Tom takes your bike, you no longer have agency over the decisions on how to use your bike. The key to objective morality is consent. Consent is the agreement between two or more people to allow decisions about one's property to be made by others. In the example above, if Tom took your bike with your consent, you have made the decision concerning the use of your property, to be delegated to Tom. It can be said that Tom has not violated your property. If Tom took your bike without your consent, then he has violated your entitlement by removing your agency to make decisions concerning the use of your property. It can be said that Tom has violated your property.

Humans are incapable of consenting to have their property violated. The violation of property, is, by definition, non-consensual. Consent represents the agreement between (at least) two parties, one requesting access to the property of the other and that access being granted without the use of aggression. Genuine consent must occur without aggression. Aggression violates property entitlement by removing agency from the owner. This is the definition of non-consent. The absence of consent is non-consent. If property is controlled by someone other than its owner without the owner's consent, the owner's agency has been removed and the property has been violated.

All humans, in all interactions, either consent or do not consent. Universally, all humans oppose the use of their property by others without consent. Consciously agreeing to use of one's property by others is consent. Conscious non-opposition to the use of one's property by others is also consent.4 Morality germinates from this distinction between right and wrong and this morality is objective precisely because it is and must be universal. It is not possible for one to neither consent nor not consent to the use of one's property by others.

Assume Tom is in a coma. Bob asks Tom if he may use his bike. In his physical state, Tom is unaware of the request and is unable to consent. His lack of consent is, by definition, non-consent. Assume now, that Tom is able to hear Bob's request, but, in his physical state, Tom is unable to respond, even though, in his mind, he gives consent. If Bob goes ahead and uses Tom's bike, even though Bob isn't aware of Tom's consent, Bob has not violated Tom's property.

Assume Bob has a bike which he no longer uses. Bob has no interest whatsoever in the bike. Tom asks for consent to use the bike. Bob genuinely doesn't care if he uses it. He answers, "I don't care." This is consent. He does not oppose Tom's use of his property, delegating his decision-making agency to Tom.

Assume a man who ardently rejects the notion of property, Tom, is sitting in the park. If Bob punches him in the face, Tom will either consent or not consent to being punched. Tom must, as a condition of being human, consent or not consent. Consenting or not consenting is an involuntary reaction among humans. Even if Tom doesn't act, he still must consent or refuse consent, even if only in his mind. If, even as an emotional reaction, he objects to being punched, then he is refusing consent. If he has a negative emotional response, but is more dedicated to his beliefs than he is opposed to the punch, then he consents. If he agrees to be punched, even on an emotional level, he consents. If he does not agree to be punched, even on an emotional level, he refuses consent. If he doesn't want to be punched, but does want to demonstrate his anti-property philosophy more than he objects to the punch, he consents.

Similar to the example of Bob who does not care about his bike, Tom also cannot remain neutral. Even if he truly does not care if he is punched or not, he is giving consent for Bob to make Bob's own decision concerning Tom's property (Tom's face). Despite Tom's anti-property philosophy, Tom's consent or lack of consent reflects Tom's innate acceptance and understanding of property. Since property is an innate feature of humanity, it is impossible for him to avoid consent or non-consent.

This is objective morality embodied in the philosophy of libertarianism.

For contrast, let's return to the idea of subjective morality. Morality becomes an issue when there is a question of right and wrong. Bob may feel, based on his values, that it is bad to be wealthy and not give to the poor. This is a perfectly legitimate moral stance (it doesn't violate objective morality) and Bob is entitled to apply this to his life and/or try to convince others to adopt his morality. But this morality is subjective; it is based on Bob's personal values or preferences. A wealthy person does not violate the property of a poor person by declining to give to the poor person, therefore, it is not objectively immoral.

Almost every person has their own, subjective moral code; things one thinks are right or wrong according to their own values. As long as one avoids objectively immoral actions, one may legitimately act according to his own subjective moral code.

Now that morality has been explored let's return to the questions raised by previously defining aggression.

Fraud

Aggression can be two things: the initiation of (physical) force, or fraud. In the initiation of force, an aggressor employs physical force against the property of others without consent, violating their entitlement. In fraud, an agreement is made to exchange property (or the value from the use of property), with one party not fulfilling his end of the agreement. In this arrangement, one party consents to the use of his property (conditionally) in exchange for compensation. He does not consent to the use of his property without compensation, therefore, if compensation is not made, his property has been used without his consent, which is a violation of his entitlement.

Compensation

By violating the entitlement to the property of others, an aggressor implicitly agrees that property need not be respected. By violating his victim's property, thereby transferring value from the victim to himself, he creates a claim on his own property by which the victim may attempt to recoup the value taken from him. Because the aggressor has agreed, through his aggression, that property need not be respected, the victim is within his entitlement to use his property in defense of his property, or to recoup his property, even if this defense requires the use of force against the property of the aggressor.

The transfer of control of a victim's property to an aggressor doesn't transfer ownership to the aggressor. The original owner had, at the time the aggression occurred, the highest claim to the property in question and because he did not consent to his property being transferred, a moral infraction has taken place. The victim retains ownership of the property, therefore, and may do with his property what he wishes, which may include retrieving it from the aggressor.

The aggressor has created a claim on his own property by non-consensually appropriating the property of his victim and has demonstrated that he does not accept that property should be respected, which includes his own property.5

In this respect he gives consent to the use of his property. Therefore, there is no moral problem in using force to recoup the property of the victim.

What, exactly, is the victim entitled to?

Value is subjective. The value of property depends on the preferences and values of the beholder. All humans use the means available to them to achieve their goals. These goals are unique to the individual. Therefore, resources will be valued differently by different people at different times, or may even be valued differently by the same person at different times. Because of the subjectivity of value, only the victim is able to determine the value taken from him by an aggressor.

Threats

The next section is controversial. I think it's best to pause to explain the importance of maintaining the independence of philosophy from practicality. Often, attempting to follow pure logic in philosophy can result in what appears to be unreasonable or untenable applications in the real world. In a philosophical exercise like this one, we are attempting to uncover logical truths, or the principles dictated by logic. These logical exercises are not subject to the constraints of any current reality. The goal is to reveal logical truth to provide guidelines for life in the real world.

Above, I explained that only a victim can determine the value taken from him by an aggressor, due to the subjectivity of value. Logic dictates that the victim could determine that the value taken from him by the aggressor is massive in comparison to the aggression. Maybe a starving Tom steals an apple from Bob's apple tree. Bob claims that the tree is sacred to his religion and must never be touched by another and Tom's transgression has not only resulted in the loss of an apple, but in a severe religious sacrilege and the psychological insecurity arising from the notion that Bob's tree is not as safe as Bob thought. Bob claims that Tom, who owns nothing, and is, in fact, starving, should compensate Bob with 1000 ounces of gold, a security canopy built over Bob's apple tree and 100 apples. As unreasonable as it seems, Bob’s claim is, philosophically, legitimate, as only he can determine the value taken from him by Tom. However, the practical reality is that he will never be able to get what he wants from Tom. A compromise will have to be negotiated.

Just because philosophy allows for a certain result does not mean that result will manifest in reality.5

Keeping this in mind, the next section will focus on threats and why they do not constitute aggression.

We've learned about what aggression is, and nothing more is necessary, but I think it's a good idea to address a ubiquitous misconception that, improperly understood, undermines libertarian philosophy.

Threats do not constitute aggression. That sentence tends to activate emotional bias. Generally the audience bursts into practical objections forgetting that the topic is not practical, but philosophical, and that philosophy should remain independent of practicality.

No matter how ardently one threatens another, property is not violated. Even if someone has a gun to your head swearing that if you move, they'll shoot, that, in itself, doesn't stop you from doing anything. You can still go about utilizing your property as you would otherwise. The fact that threats don't violate property is the most important point, but there’s more worth looking into.

Threats are subjective. If a man has a gun pointed at you, threatening to shoot, and he's 1000 miles away, is that a threat? What if he's 10 miles away? What if he's 1 mile away? 500 feet? 50 feet? 1 inch?

At some point along the above progression, most people went from “not a threat” to “definitely a threat.” But it should be clear that those judgements are not based on logic, but on the values of the observers. You can't have a philosophical principle that's completely subjective, especially when it comes to the violation of property, which is what most people advocate in response to threats.

If a threat is perceived, and it's up to he who perceives the threat to decide to act upon the property of the threat maker, then the violation of property is justifiable under virtually any circumstance imaginable. He who perceives the threat doesn't actually know the intentions of the perceived threatener. Until property is actually violated by the threatener, his intentions cannot be known. Because intentions cannot be known, all people can, at all times, legitimately be considered threateners. It could be that the man standing quietly on the sidewalk is more of an actual threat than the man pointing a gun at you. Additionally, a threatener may himself be unaware that he is a threatener. How? Because accidents happen. All people, at virtually all times, represent some level of threat to someone without having actually violated anyone's property. Therefore, it is morally wrong to act upon a threatener’s property without consent.

In order to avoid rejection of this idea due to emotional bias, I will take a tangent into practicality for a moment. Remember how Bob was unable to get what he wanted from Tom after Tom stole Bob's apple, due to the impracticality of his request? A similar idea can be applied here. Assume Tom points a gun at Bob and swears he's going to shoot because he's upset about what Bob's trying to get from Tom for stealing his apple (a good reason to avoid seeking unreasonable compensation). Really, Tom's just frustrated and upset and lashing out. But he's really a good guy who's having a hard time. Bob doesn't know that. For all Bob knows, he's about to be dispatched by a crazy person. So Bob initiates force against Tom in self defense. Bob is successful and Tom's threat is neutralized. Bob, of course, is the aggressor in the situation because he initiated force against Tom's property. So Tom has a rightful claim against Bob for his violation. Tom goes to Judge Jim to decide the case. Judge Jim, being familiar with the correct philosophical understanding, decides that Tom is right and Bob has violated his property. Tom wants Bob to compensate him with 1000 ounces of gold and 100 apples from Bob's tree. Judge Jim has something to think about: his career as a judge is based on his understanding of philosophy, his fairness in his judgements and how the market, the final arbiter, perceives him as a judge. He doesn't want to be seen as unfair or his career could be endangered. He realizes that Tom's threat was reckless and immature. He realizes that almost everyone, including himself, would have reacted as Bob did. So, in accordance with correct philosophy, Judge Jim rules in favor of Tom, but refuses to award him the compensation he seeks. This way, Judge Jim rules fairly and protects his reputation in the eyes of his market. This is a hypothetical example of reality limiting the extremes of philosophy.

Just because philosophy allows for a certain result does not mean that result will manifest in reality.5

Force in Defense

Though the NAP has been explained, I'd like to go a little further into some unnecessary territory to expand on the ideas of aggression, particularly the use of force in defense.

Earlier, the justification for the use of force to recoup property was explained. The same is true in defense of property. The only difference is time. To recoup property, the transgression has already occurred. To defend property, the transgression is currently happening. Once a threat is realized and becomes aggression, a victim may morally employ force to defend his property. The amount of force he is justified in using is unlimited. Practicality will impose limits and incentives to avoid the use of excessive force, but philosophically, unlimited force is legitimate.

To claim that the legitimate use of force in defense is limited requires the application of subjectivity. If Bob catches Tom stealing his apple, no matter how much or how little force Bob uses to stop Tom will be considered by different people to be too much. How much force is necessary depends on the values of the observer.7

Suppose Bob sees Tom violating his property and shoots and kills Tom in order to defend it. Most people would agree that Bob's use of lethal force to defend his property against a minimal violation is unreasonable. Economist and philosopher, Murray Rothbard, addressed this question with the concept of "proportional force." Rothbard's idea was that one has the right to defend his property with whatever amount of force is necessary to repel a violator, but no more.8

In other words, he may use "proportional force;" force in defense proportional to the force used by the aggressor. Proportional force may be a fine practical guideline, but because proportional force is subjective, it can't be used as a moral principle.

Similarly, Bob may use any force he chooses to recoup his apple if Tom gets away with stealing it, though there is a subtle but interesting difference. Tom has effectively told Bob that he doesn't respect property, which, logically, must include his own, thereby he gives consent to the use of his property without conditions. Conditionless consent frees Bob from moral constraint. The interesting part is that if Bob needs to use force to overcome Tom's defense of his ill-gotten gains, Tom puts himself in a logical circle; if he wants his (and, therefore, other's) property to be respected, then he should cease his defense and return Bob's apple. If he does not want property to be respected (which includes his own), as he has demonstrated by stealing Bob's apple, then he should also cease his defense of his property, since he approves of property violation and Bob is violating his property! Of course, I'm using the term "violating" loosely here; Bob has a legitimate claim to what Tom possesses, so it's not really a violation of Tom's property.

What about the use of force in defense of others?

Tom was attacked by Mean Mike. Bob saw the attack and rushed over to help Tom. Bob grabbed Mean Mike and pulled him off of Tom.

Mean Mike did not consent to Bob's imposition on Mean Mike's property. Mean Mike did not aggress against Bob. In the context of the NAP, what has happened?

It's clear that Mean Mike has violated the NAP by violating Tom's property (his body). By violating Tom's property, Tom now has a claim to Mean Mike's property to compensate for the value Mean Mike has taken without consent.

Bob initiated force against Mean Mike in defense of Tom. What does that mean?

Mean Mike has violated Tom's property. Therefore, Mean Mike has openly demonstrated that he believes property (which necessarily includes his own) need not be respected. He has, in effect, consented to the use of his own property by others6. This is Bob's out. Because of Mean Mike's consent, Bob may impose himself on Mike's property.

But only to an extent.

Mean Mike's property is now Tom's property to an as-yet unknown degree because Mike's violation of Tom's property has created a claim on Mike's property. Because value is subjective, we don't know the extent of Tom's claim. So if Bob takes too much liberty with Mike's property, he risks violating the NAP against Tom if he infringes on Tom's claim to Mike's property.

Bob's defense of Tom, in itself, does not constitute a moral transgression, a violation of the NAP. It does, however, put Bob at risk of violating the NAP if he infringes on Mean Mike's property to the point that it damages Tom's claim to Mike's property. It may be that, even if Bob did violate the NAP that Tom would forgive him in gratitude for his help in subduing Mean Mike, but defending the property of others is not immoral.

Accidents

Aggressors don't always aggress intentionally. Probably far more often than not, when property is violated, it is violated by accident.

Regardless of an aggressor's intent (which, by the way, is unknowable), aggression transfers value, non-consensually, away from a victim. In the event of an accident, value is typically transferred away from the victim, but is not captured by the aggressor. In most accidents, the value is simply lost.

Still, the victim is owed compensation by the aggressor and all of the principles above apply.

Bob is driving his battle tank through the Ancapistani countryside, his steering malfunctions, he loses control, drives off the road and damages Tom's mailbox.

The principle is that Tom has a claim on Bob's property now that Bob has destroyed the value of Tom's property. Regardless of intent (intent is unknowable and should never factor in to the discussion) one person violated another's property. The extent of that claim is a practical matter. A matter that will have to be decided somehow taking into account the subjective valuation of the property damaged (if Bob had no property, Tom would have a claim on Bob's future property).

The victim has a claim on the property of the violator. Once restitution is made, however, the claim is no longer valid.

The point of all of this has been to fully understand the philosophy behind the principle of libertarianism, the NAP, to a level previously unattained. The reason this understanding is so important is because libertarianism is the only objectively correct social philosophy. The extent to which libertarianism is not understood and adopted is the extent to which society will suffer. People can't be expected to adopt philosophies that they don't understand. Though this essay is dry and most people won't understand it anyway, my hope is that intellectual libertarians will be able to adapt the concepts here to be more everyman-friendly.

The concepts explained here will be controversial, even among libertarians. So, at the very least, if they are mistaken, hopefully, they will spark enough quality thought to reach better conclusions. Obviously, this exercise was undertaken because the fine details of libertarianism aren't sorted out to the level that they can be and should be.

The philosophy above is meant to put libertarianism out of reach of other philosophies, and, in fact, they are intended to make libertarianism philosophically bullet-proof. It was already bullet-proof from a utilitarian, consequentialist, or practical standpoint, and, whether through this essay or some other, philosophy should reflect reality, and hard philosophical libertarianism can and should be indomitable.