Main article from Victor Yarros:

Looking over the field of Anarchistic activity, methinks I see a great danger forthcoming. Anarchism is becoming "respectable." The "philosophical" and "pacific" Anarchist of the Liberty type have lately been taken kindly to and shown much sympathy by a sort of people whose friendship would be the greatest misfortune and disgrace to any serous movement. These are friends that Liberty must be saved from. "Another such victory, and we are lost!" The cause of this love an patronizing cordiality is to be found in the fact that Liberty vigorously denounced the actions of the Chicago and New York Communists, and dates its origin from the time those utterances were made, utterances that have brought much comfort to the reaction and that were gloriously soothing to the troubled hearts of the property beasts.

I do not wish to be understood as opposing the position Liberty has taken on the question of force, nor as criticising the form in which the protest has been expressed. Liberty wages relentless war against all forms of tyranny and compulsion, and, whether the assaults on individual liberty are made by soulless schemers in the name of "law and order" or by sincere, self-sacrificing, but misguided, friends of liberty and justice, the principle is the same in both, and the true Anarchist is bound to condemn it in either. The Anarchist is the antipode of the partisan, and will never hesitate to express his real sentiments, even if by so doing he strengthens the hands of the enemy.

But, having done his duty, the Anarchist should make it clear to the oppressor that he knows how to discriminate between a bitter foe, to whom no mercy is to be shown and no quarter given, and a friend, whom we do not cease to love and honor despite the severe reproof and censure we may be compelled to pass upon his hasty and irrational actions. I fully agree with friend Tucker that violence is no remedy for social evils, and that reformers should appeal to the intelligence and "better nature" of the victims of our monstrous system rather than to the baser passions and low instincts of the human being. I heartily endorse every word he said in regard to the peculiar ideas and methods of the "Alarm" and "Freiheit" school. But more than I abhor unnecessary violence do I detest Christian meekness and all-forgiving love in a radical. Too much force is decidedly wrong; but too little force and a Quakerish opposition to it is still more repulsive to manliness and the spirit of justice. In consequence of Liberty's hostile attitude toward the Anarchistic Communists, who have made life extremely unpleasant to some people, Anarchism has come to be regarded as a very harmless thing, a sort of spiritual amusement for kid-gloved reformers, which need not in the least interfere with business and the pursuit of pleasure, as it dos not deal with the here and now. Clergymen, capitalistic editors, and labor reformers begin to smile on "philosophical Anarchy." pronounce it a very sweet and charming thing - to be realized a thousand years hence; some kind people go so far as to admit that Anarchy is the Christian ideal, the millennium, the "triumph of law and order." At any rate, it is agreed that Anarchism is no factor in the labor movement, and that neither good nor harm is to be expected from it. Indeed, can there be any objection on the part of those who own the earth to the existence of a class of cultured visionaries who love to dream about a perfect state of society, of a time when crime and vice will have disappeared from the fact of the earth and all men will be perfect and wise?

Shades of Proudhon and Bakunin! Is it for this thart you lived and worked? No wonder that many of our best friends are disgusted. Now, as one of the "philosophical Anarchists," I protest against this misrepresentation of Anarchism.

Anarchism means war - war upon all government,

all authority, and all forms of slavery.

We have a right to use force and resist by all means the invasion of the self-constituted rulers, and we shall not hesitate to bring into play the "resources of civilization" when necessity calls for it and when maddened authority leaves us no alternative. We are all "rebels to the law," and the monopolists and the prostituted editorial Mammon worshippers need not favor us more than they do the Chicago "fiends." The followers of Liberty are even more dangerous to "law and order" than the bomb-throwers, and, judging from certain indications, we may be compelled to do a little bomb-throwing before long. Let tyranny beware, and let respectability undeceive itself!

Victor Yarros

Response from editor Benjamin Tucker:

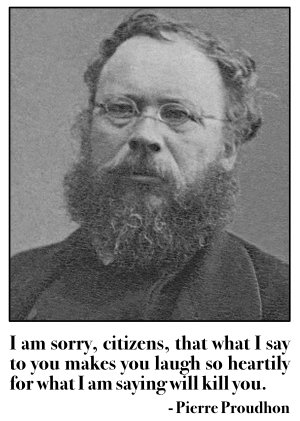

While giving hearty assent to what I take to be Mr. Yarros's general meaning in the above article, I desire to be a little more explicit. The words "philosophical" and "pacific" do not trouble me, no matter who applies them. They certainly correctly describe the attitude and methods of the individualistic Anarchists; why, then, object to them? If there are those who choose to smile patronizingly or contemptuously upon these methods as harmless (I confess I have not seen so much of this as Mr. Yarros seems to find), I simply answer them with the words of Proudhon to the French Assembly of 1848, which grew hilarious over his remarks: "I am sorry, citizens, that what I say to you makes you laugh so heartily for what I am saying will kill you."

It is because peaceful agitation and passive resistance are, in Liberty's hands, weapons more deadly to tyranny than any others that I uphold them, and it is because brute force strengthens tyranny that I condemn it. War and authority are companions; peace and liberty are companions. The methods and necessities of war involve arbitrary discipline and dictatorship.

So-called "war measures" are almost always violations of rights. Even war for liberty is sure to breed the spirit of authority, with after effects unforeseen and incalculable. Striking evidence of this is to be found in the change that has taken place, not only in the government, but in the people, since our civil war. There are times when society must accept the evils and risks of such heroic treatment, but it is foolish in the extreme, not only to resort to it before necessity compels, but especially to madly create the conditions that will lead to this necessity. Taking this view of the matter, I cannot quite approve Mr. Yarros's distinction between "too much force" and "too little force." As a general thing, when force becomes necessary, the wiser way is to use as much as possible as promptly as possible; and, until it becomes necessary, there cannot be too little force. This is the policy of Liberty, and its editor will pursue it with the same serenity and steadfastness, whether the clergy contemptuously call him "philosopher" or the Communists angrily call him "coward."

As Mr. Yarros has coupled my denunciations of the New York and Chicago Communists, I wish to explain that I make a vast difference between the motives that govern these two classes. The New York firebugs are contemptible villains; the Chicago Communists I look upon as brave and earnest mean and women. That does not prevent them from being equally mistaken.

Benjamin Tucker - Editor of Liberty